Julie Ha and Eugene Yi Transnationalize the Roots of Anti-Asian Hate in ‘Free Chol Soo Lee’

Asian/American films incepted out of the impulse to speak back, and perhaps more critically, they carved a political space to speak from. First-time directors Julie Ha and Eugene Yi’s “Free Chol Soo Lee” (2022) harks back to the same fire held in earlier Asian/American documentary films, such as Curtis Choy’s “Fall of the I-Hotel” (1983) and Renee Tajima-Peña and Christine Choy’s “Who Killed Vincent Chin” (1982) where filmmakers turned to storytelling to embrace the Asian/American political identity.

The film follows the life of Chol Soo Lee, a Korean refugee who was falsely convicted for the 1973 murder of a local gang leader in San Francisco Chinatown. Judges racially profiled and wrongfully arrested Lee, indicting him with a life sentence in prison.

While Chol Soo Lee was in prison, he was involved in a physical altercation where he murdered another inmate out of self-defense, which landed him another criminal charge and placed him on death row. Chol Soo Lee would spend the next decade of his life in prison, three of those years on death row, all because of a hasty conviction withheld of substantial evidence and witnesses.

Four years into Chol Soo Lee’s imprisonment, Korean journalist K.W. Lee published an investigative report on the San Francisco Chinatown case in The Sacramento Union, the oldest daily newspaper in the region. K.W. Lee believed Chol Soo Lee was innocent, and for the first time, Chol Soo Lee felt as if his truths were spared. “I finally have a chance to say I’m innocent. [K.W. Lee] had single-handedly gave me hope, when there was no hope,” Chol Soo Lee wrote in his memoir.

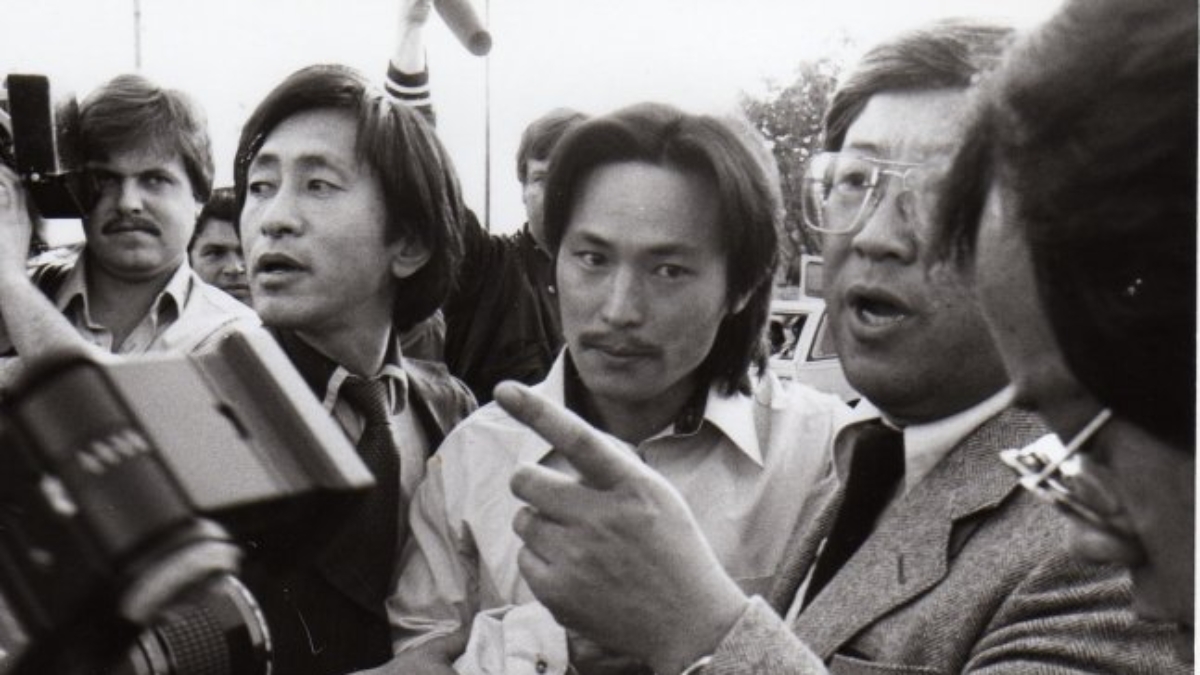

After K.W. Lee’s report notified the public about Chol Soo Lee’s wrongful conviction, Korean/American community members – as well as Asian/American supporters at large – galvanized to secure a new trial for Chol Soo Lee to eventually exonerate his charges.

Led by lawyer Jay Kun Yoo, schoolteacher Grace Kim, and K.W. Lee, a Defense Committee was created in support of Chol Soo Lee’s release, where they used Korean churches as strategic sites for community mobilization. Student organizers who became radicalized during the Third World Liberation Strikes also organized and collected signatures from the campus community, fundraised (albeit unsuccessfully) by selling baked goods and hosting dances, and spread the word about Chol Soo Lee’s wrongful accusation through political posters, conversations, and even a poem-turned-song about Chol Soo Lee’s trial. The photographs we see of Korean grandmas protesting next to Asian youth, of elderly Korean church leaders collaborating with student organizers, shows how the Chol Soo Lee case ignited not just a pan-Asian, but an intergenerational solidarity movement grounded in mutual care.

One of the most remarkable aspects of Ha and Yi’s documentary film is the extensive amount of archival footage used throughout. Much of the footage and photographs used to create a panorama of Lee’s case were from Asian/American community members and organizers that were present during the movement. “K.W. [Lee] was the person that opened so many doors and introduced us to people in the movement,” Director Yi told me. “It was fun to see the slow accretion of material that people had and gave the seed that there was an unofficial, underground archive of Chol Soo Lee material that were kept by people that were there and always have been.”

With a seamless blend of archival footage, voice-over-narration of Chol Soo Lee’s letters, compelling animation, and present-day interviews, the film serves as an act of memorial restoration, ultimately returning agency to Chol Soo Lee’s life. “If it wasn’t for everything [organizers] had done back then, we wouldn’t have anything to speak of now. It really is an honor and privilege to extend on what they did,” Yi said.

As much as Chol Soo Lee was iconicized for the Chinatown case, Ha and Yi made sure to share his story holistically – from birth to death. “Telling Chol Soo Lee’s full story became our North Star,” Ha shared with me. “It felt like the spirit of Chol Soo Lee wasn’t at peace.”

The film shows Lee’s beginnings during the remnants of the Korean War, also known as the “forever war” or “forgotten war,” and ends with Lee’s life until his death post-trial. As a son of war and a victim of mass incarceration, Lee’s life was haunted with grief, leading him to patterns of misfortune. In particular, he struggled to adapt to society after his prison release, suffering from unemployment and eventually drug addiction to cope with his traumas. He would later join a gang, where an arson job-gone-wrong led him to severe third degree burns on his body and face. In one section of footage in the film, K.W. Lee speaks at Chol Soo Lee’s funeral in 2014, where he says: “When I look back, he died a hundred deaths in that goddamned living hell called the California prison system. And even in freedom, in the free world, he suffered a thousand deaths.”

Nine months before the making of the documentary, Ha had attended Chol Soo Lee’s funeral with plans to write an obituary for KoreAm magazine. “While I was in this space, I felt an emotion that was beyond grief. It felt like a heaviness. Many of the people there were activists that had come to Chol Soo’s aid forty years earlier. A couple of them were expressing such deeper regret that he hadn’t lived a happier life,” shared Ha.

For Ha, who witnessed the grief carried during Chol Soo Lee’s funeral, including her own journalism mentor, K.W. Lee, she was compelled to rectify the history of the Korean/American community. “There was one point in the funeral where K.W. Lee stood up, and he was clutching this Buddhist monk’s walking stick that Chol Soo had carved for him, and he said, ‘Why is this story still underground?’ And he lamented how this landmark Asian American social justice movement had been forgotten,” Ha shared. “Fast forward nine months later, Eugene and I are talking, and we felt like this story and this history needed to be known. So that’s when we decided to dive in. It felt like our generational responsibility to tell this story.”

Ha and Yi also share that the narrator of Chol Soo Lee’s memoirs, Sebastian Yoon, was a critical aspect to the film’s narrative process. As a formerly incarcerated Korean, Yoon deeply empathized with Lee’s experiences, carrying Lee’s story as a mirror to his own inner feelings of loneliness while in prison. Ha shared with me, “[When] Sebastian read Chol Soo’s memoir, he was able to help us identify different aspects of Chol Soo Lee’s incarceration. How that experience is not just prison violence, but internal trauma of depression and loneliness and isolation.” Ha also shared that Sebastian did not want the audience to view Chol Soo Lee’s life imperfectly, but to extend empathy to everything he was forced to undergo.

Unlike Vincent Chin, Chol Soo Lee’s life is relatively unspoken about. This may be because Lee, unlike Chin, had criminal charges before and after his release from prison, which removed him from the image of a ‘perfect’ victim the justice system so-often renders people into. As Ha and Yi show us in this film, however, Chol Soo Lee was never a criminal; he was someone who was criminalized. He was born as a result of rape during the height of the Korean war, physically abused by his mother (who was also a victim of her own right), alienated from the majority Chinese diaspora in San Francisco Chinatown, and struggled to learn and adapt to the unfamiliarites of English. Lee was stripped of the autonomy to simply live; he was forced to survive.

After watching Ha and Yi’s remarkable film, I learned that, although Lee’s life was grooved with grievance and loss, he is not defined by the pains he carried or the pities he received, but rather the care and joy he extended to those he touched. Because despite all the struggle Lee underwent, he still carried within him an “innate friendliness,” as K.W. Lee described in the film, that had rippled across the hearts of many Asian/American community members who stood alongside his release. And to this day, Lee’s life stands as a touchstone for Asian/American politicization, and beckons us to pay attention to the ways in which anti-Asian violence aren’t ahistorical feelings of ‘hate,’ but rather an ongoing project of violence that spans back to imperialist militarized aggression abroad; and the violence domesticates itself through mass incarceration, deportation, and surveillance ‘here’ within the borders of the United States.

“We hope people can draw inspiration from what happened and our history,” shared Ha. And as we remember and draw the present from the past, we will perhaps, finally, be able to set Chol Soo Lee free.

“Free Chol Soo Lee” screened at the 45th Asian American International Film Festival.