‘Photographic Justice: A Corky Lee Story’ is about a man and the movement he pushed into the limelight

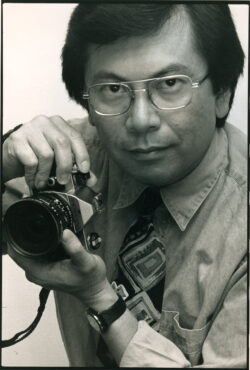

Young Kwok Corky Lee, otherwise known as “Corky,” took photos that to this day, like the Brooklyn Bridge, connect two different societies. Born in 1947 as part of the Baby Boomer generation, Lee had a typical American upbringing and recognized the power of images at a young age. Still, it wasn’t until his college years when he started meeting other Asian Americans, and began to form his identity as an activist. Mainstream America was not used to viewing print media from the viewpoint of a person who looked like Corky. In “Photographic Justice: A Corky Lee Story,” Jennifer Takaki follows Lee being a master in his element. The pace of the documentary walks briskly like a busy New Yorker, rushing through a flurry of historical events through the eyes of one man, while allowing for time to pause and reflect.

Takaki, a fourth-generation Japanese American, spent 19 years of her life trying to produce a documentary about the fascinating life of Corky, even after his unexpected death from COVID. His contributions to the community were so huge, people gathered on the streets of Chinatown to mourn his passing. “The sheer presence of Corky [at community events] was because… if he wasn’t there, he knew it wasn’t going to, in a lot of cases, get documented,” said Takaki. What made his work stand out was the way he went about it; the community “could see how genuine his intent was and how much he cared for the events and why he was there.”

The documentary includes animation to illustrate a recall that Corky would have. One of which is a personification of the way people started calling Corky by the nickname: “Corkypedia.” Takaki remembers him by the way “you could talk to him about anything, [even] the weather, and suddenly he’ll start talking about Asian American history, somehow.” Corky was a second-generation Chinese American by way of Toisan province, but Takaki thinks “why his work is so significant is because he was transcending all these different cultures at a time when no one really left their own ethnic identity. [If you were Japanese], you hung out with Japanese, [if you were Chinese], you hung out with Chinese … back in the 70s. Corky was different.”

A word to the wise regarding the way Takaki was able to collect Corky’s material all the way from the 70s until now: “It just evolved over time … when we went to events together, he would hand over those photos, and I would scan them and return them. I wanted to show Corky back in the 70s, and so I started asking different archives and I would go to different activists … for videos to Corky’s photos.” Takaki was committed to telling the story as thoroughly as possible, from start to finish.

“Photographic Justice: A Corky Lee Story” screened at the 46th Asian American International Film Festival.