Special thanks to Paul Chhorm, Robert Chau, Eng Tang, Avian Munoz, Chaiya, and Monika for sharing your stories. This wouldn’t have been possible without you.

On November 2, 1984, Rolland Joffe’s “The Killing Fields” hit theaters in the UK. The film, which tells the true story of two journalists — Cambodian Dith Pran and American Sydney Schanberg — covering the Cambodian Civil War and subsequent genocide, was a critical darling, and won three Oscars. Most notably, “Best Supporting Actor” for Dr. Haing S Ngor, who played Pran, and who’d never acted beforehand. However, in the 40 years since its release, the film, the true story, and Ngor have faded from public consciousness. This should be remedied. Not only does the film still work, but it still holds great significance for the Cambodian diaspora.

For some, like Paul Chhorm, who survived the genocide himself, it’s the first movie they ever saw. As he explained to me when I visited the National Cambodian Heritage Museum and Killing Fields Memorial in Chicago, “‘The Killing Fields’ is the first movie I saw in my life […] so it was pretty moving in terms of the storyline. And even though I was a child, it just reflected all the hardships that a child can see, like hunger, especially, and the corpses.”

His sentiments were echoed by another survivor, Robert Chau, who was 16 when the genocide ended, and who explained over email, “[the film] takes me back to a brutal time in my life I tried to forget. For some people it’s just entertainment. For me, I actually lived it.” Even the grandchildren of survivors, like Avian Munoz, find the film difficult to watch. As he clarified over email, “I have watched the film three times and it always keeps me awake at night for weeks.”

As difficult as the movie is to watch, some Cambodians find it an effective means of processing their trauma, and have even turned viewing it into a ritual. One member of the diaspora from Greater Philadelphia, Chaiya, whose parents had to flee the country in the 70s, described how the film’s journalistic format allows his family to work through their pain. As he explained in an email interview, “This was probably the only movie my parents could watch because of the format.” And another member of the community from Lowell, Monika, who lost both grandparents and her older sister to the genocide, informed me of how some Cambodians view the picture almost religiously. “One of my mutuals on Letterboxd, [another Khmer woman],” she explained over email, “watches the movie every year.”

This flick is special, not just in terms of having an Asian lead, or telling a little-known story in the West, but in terms of a unique structure that still holds up. To understand why, though, we need to go over some history.

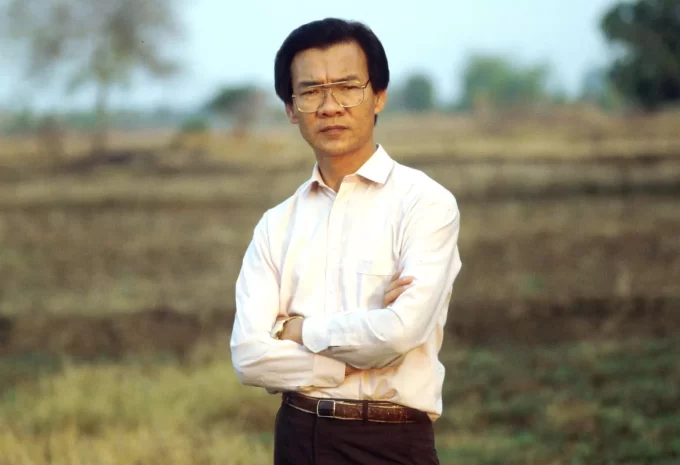

In 1975, the Communist Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot, seized control of Cambodia, and, over the next four years, they carried out one of the worst genocides in history, killing over a million people. Some estimates put the death toll as high as 3 million. Everyone within Cambodia’s borders was impacted, including a gynecologist named Haing Ngor, and a journalist named Dith Pran. They didn’t know each other yet, but they suffered many of the same hardships. In time, their fates would become intertwined. In 1979, both men fled to Thailand, and from there, they made their way to the United States. There, Pran reunited with his wife and children, and became a photographer for the New York Times. Ngor, for his part, would be unable to resume his medical practice, and would never remarry.

By the early 80s, Pran’s story had become so well-known that producer David Putnam and director Roland Joffe wanted to adapt it to film. They even wanted to call it “The Killing Fields,” a term that Pran himself coined to describe the horrors he’d seen. This is where Ngor re-enters the picture. Despite having never acted, he was spotted at a Cambodian wedding in Los Angeles in 1983 by the film’s casting director, and asked to star in the movie. While Ngor wasn’t initially interested, he decided that this would be a chance to tell his country’s story, and bring attention and aid to those still suffering.

The 1980s saw the release of several Vietnam War-related films, including “Platoon,” “Good Morning, Vietnam,” and “Born on the Fourth of July.” Some filmmakers, like the people behind the “Missing In Action” and “Rambo” franchises, sought to give America its mojo back. Others, like Oliver Stone and Brian De Palma, tried to expose Americans’ brutality. But one thing none of these films did was consider the perspective of the Vietnamese or Cambodians, who were almost always reduced to the role of incoherent victims. And few, if any, of these movies provided exposition on why the war began, or what its long term consequences were. As Munoz put it, “Most Americans have very little understanding of the series of administrative blunders that led to the Vietnam War, and an even poorer understanding of how that directly led to the Cambodian genocide.” That’s why “The Killing Fields” is so unique. Not only does it address how American actions in Vietnam destabilized Cambodia, but Haing Ngor is unquestionably the lead. And he’s absolutely terrific, displaying both nuance and confidence on screen.

This flick doesn’t work without Ngor, and his importance goes beyond just giving a great performance. He gave a face to the Cambodian diaspora, and many, like Chau, watched the film for him. As he explained over email, “I watched [the movie] when it first came out because [Ngor] was a friend I knew through the Khmer community.” And Ngor would repay his community’s support. Not only did he work as a counselor at a refugee resettlement center in LA, but he also built an elementary school and operated a small sawmill that provided jobs for local families. One can only imagine the good he could have done, and the other great performances he could have given. Alas, Haing Ngor was murdered on February 25, 1996 in a robbery outside his home in L.A. He was only 55.

Beyond the picture’s novelty as a mainstream movie with an Asian lead, the filmmaking feels very modern. “The Killing Fields” lacks a lot of the setup and melodrama found in Hollywood action movies of the era. Aside from 40 seconds of VO at the beginning, which explains that the fighting in Vietnam spilled into Cambodia, you get no exposition on the country, the characters, or the war. Instead, you’re thrown right in the deep end, with Schamburg and Pran going up river to see an area that’s been bombed. And because several scenes lack dialogue, much greater emphasis is placed on visual storytelling.

The movie feels like a newsreel, and that quasi-documentary style makes the horrors more digestible. Chaiya found the film easier to watch than other flicks about the genocide, saying, “[My friends and family] enjoyed the movie being told from a journalist’s perspective … The movie ‘First They Killed My Father’ on Netflix was a movie that none of my parents wanted to watch. [That] felt like it was an exact POV of the events, which my parents did not want to relive.”

Now, by virtue of being just one film with just one story, “The Killing Fields” isn’t a perfect representation of Cambodian people or culture. You don’t see Theravada Buddhism being practiced. You don’t see people cooking fish amok. You don’t see the complex web of relationships between the different factions in Cambodia, and countries like China and Vietnam. And as Munoz noted, women are almost entirely absent from the story. “There are many great untold stories of how women survived and managed to save their families and loved ones,” Munoz said. A sentiment shared by Eng Tang, who survived the genocide herself, and who declared over email, “There are thousands of other experiences and important stories that still need to be told.”

All of this might explain why, when asked if the movie was a good representation of Cambodia, Chaiya responded “I don’t think it’s a good representation of Cambodian people, but it paints a horrific picture of that point in the country’s history for sure.”

Chau echoed these sentiments, but was quick to add, “Any kind of representation or education of the Khmer Rouge is good, so maybe people would learn and so that it wouldn’t happen again.”

It’s been 40 years since “The Killing Fields” first hit theaters, and both the film and the plight of Cambodia have largely faded from public memory. Which is wrong, because history doesn’t just stop. Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge might be gone, but their impact is still being felt. As Chau explained, “There is a huge culture of mistrust and jealousy in my generation because many survivors my age are still stuck in the past and still internally feel we are at war.”

Munoz noted how he’s “used to the fact that most people who know about Cambodians only know about us in the context of those four years of genocide.” And as Monika so eloquently put it, “We’re a country and a people that have been through and survived a lot and were going to be in a process of rebuilding and reclaiming our dignity and our sovereignty **forever**.” All of this has to change, and, thankfully, there have been efforts made by the diaspora to address, and move forward, from the genocide.

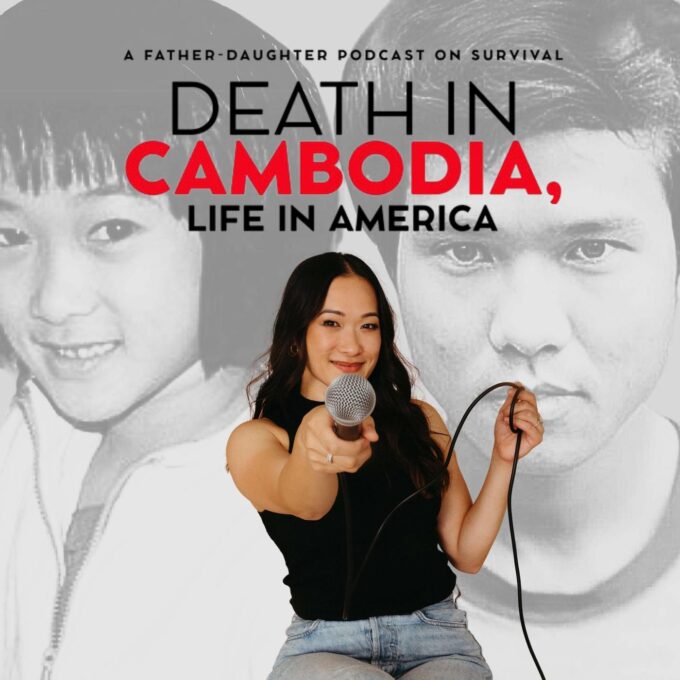

Eng Tang is currently in the process of writing her memoir, “so my family’s story of loss and survival in the Killing Fields will finally get the recognition it deserves.” Robert and his daughter, Dorothy, created the “Death In Cambodia, Life in America” podcast to share his, and other survivors’, experiences. And together with Dr. Sochanvimean Vannavuth, Dorothy started “Khmer Courageous Conversations,” a safe, community process group for Cambodian people to talk about hard topics under the supervision of a clinical, licensed therapist.

It’ll be a long, slow process, but the Khmer community will recover. And someday, hopefully, they’ll be able to leave “The Killing Fields” behind.