Written By: Kano Umezaki

This article may contain spoilers.

For decades, U.S. expansionists have branded Kaua’i as a land for leisure, primed with rich forests and vast shorelines. With its geopolitical alignment to the Asia-Pacific, Kaua’i also presented foreigners with strategic opportunities for military bases, leading to its conscription into the militarized archipelago that spans from the Pacific Coast of California and Washington to the Eastern territories of South Korea and Okinawa.

These colonial legacies of Kaua’i are intimately explored in Anthony Banua-Simon’s documentary feature, “Cane Fire,” which was co-written and produced by Mike Vass. The film historicizes U.S. commercial dominion over Kaua’i as the root cause for the fleeting import of Asian laborers, the expansion of sugar and pineapple plantations, and the eventual consolidation of a deadly tourist economy. Banua-Simon expands on this history by detailing through his own life: he tells me his great great grandmother used to work as a sugarcane farmer in Puerto Rico until a hurricane caused ruin on many of the fields, leaving some workers unemployed. “The then U.S.-instated civilian governor of Puerto Rico, Charles Herbert Allen, orchestrated a system of labor migration bringing one side of my family from Puerto Rico to Hawaiʻi in 1901 to continue to work there,” says Banua-Simon. “And that’s where my family story continued.”

As a way of further learning and connecting with his Filipino ancestry, as well as the forces that shaped their displacements, Banua-Simon interviews his family back in Kaua’i. We especially bear great details from his great uncle Henry who was raised in a segregated labor camp, working long hours in the cannery and plantation fields. He shares his experience of labor organizing with the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), where workers collectively demanded land and better wages by revolting against the Big Five sugar barons.

“It was incredible speaking to my great uncle Henry because he had lived through so many distinct periods in Kaua’i and was able to vividly recall each one,” shares Banua-Simon. “He was often very frank, but it always came from a place of care and humanity.”

As someone who experienced almost a century of U.S. corporate prowess on Kaua’i, Great Uncle Henry has seen the economic transformation of the island. He grew up during a time when commercial success hinged on intensified industrial agriculture and saw the tourist industry change the landscape of Hawai’i once more. In the film, he comments about his life’s witnessing, stating: “What about our history. How this state was formed. How this government was formed. It was stolen, most of the land.”

“I also appreciated that he was willing to talk about his perspective of being an immigrant settler without getting defensive,” says Banua-Simon. “To be in that place in his life and still be open to being curious and thinking critically was very inspiring.”

Critically examining the tourist industry, the film pays particular attention to Coco Palms Resort, which was once a hotspot for Hollywood celebrities to lounge and dine. Built on one of the most sacred sites in Kaua’i, the resort –– now abandoned –– has become the grounds for long-standing land disputes between investors and Native Hawaiian protectors. While we see Wailua activists fight for the repatriation of their lands and its memories, we see other natives who view the restoration of Coco Palms, as well as the expansion of the tourist industry, as necessary economic opportunities.

Lending himself to this conflict is Larry Rivera, a well-known singer at the former Coco Palms Resort, where he once was in the company of celebrities like Elvis Presley and Frank Sinatra. Rivera, having gained stability and fame through the tourist economy, believes investing in tourism is essential for his community’s survival. With regards to documenting the different perspectives natives have towards tourism, Banua-Simon shares: “I have a lot of respect for Larry Rivera and know he means well, that he wants others to share the same success that he found, but we wanted to focus on an energy of going forward in a new way, informed by the past but not repeating it.” Adding to these thoughts, Vass states, “This sort of clash of perspectives has become increasingly visible even in the years since we started the film, and I think it’s clear it will only become more and more unavoidable.”

The tourist economy thrives by making Native Hawaiians depend on it, and along the process, depend on the commodification of their own cultures and people. As real estate investors continue expropriating land in Kaua’i to sell –– about 50% of which are owned by non-permanent residents –– it’s difficult for Native Hawaiians to abandon their means of financial support, as if to reject the scarce opportunities by which they obtained them.

Further fueling the development of the tourist industry is media: the film shows us resort advertisements that glamorize the islands, wealthy visitors mocking Hawaiian culture (then vlogging about it) and staged fashion lines of white women dressed in appropriated Native garments. To make matters more dangerous, we also have billionaires like Mark Zuckerberg investing in Hawaiian property, where he recently bought 600 acres of land in Kaua’i for $53 million.

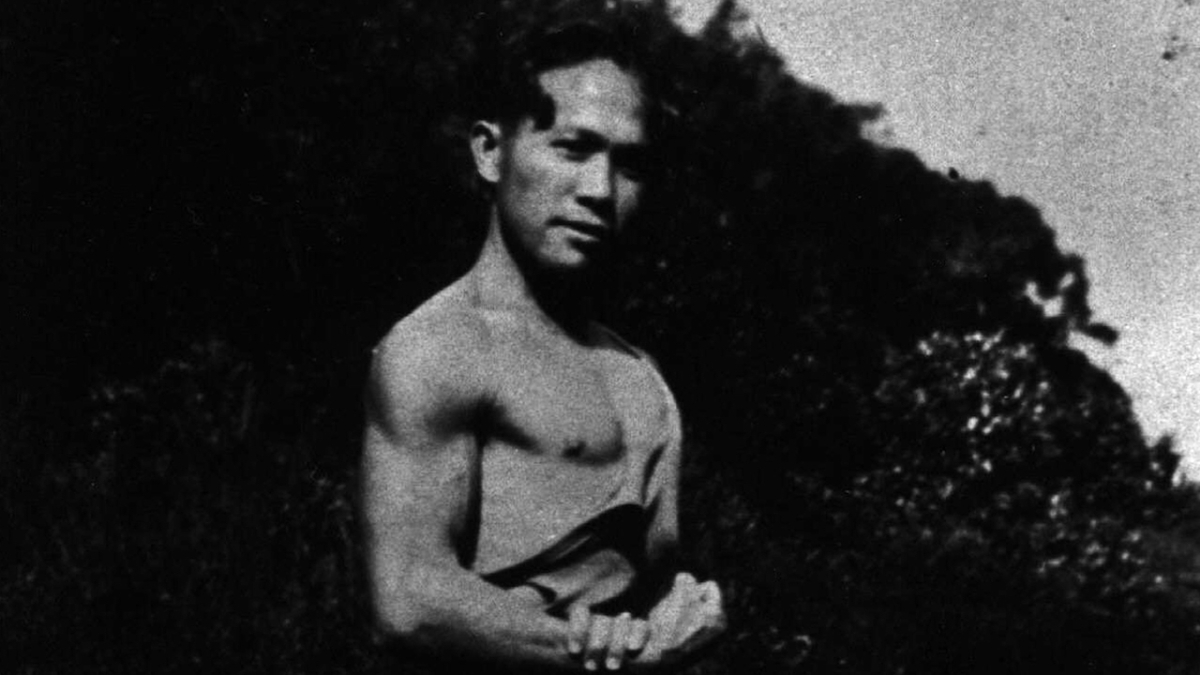

But even before the modern real estate boom, Kaua’i has long been depicted as a tropical paradise in early Hollywood films, where Native Hawaiian and Asian laborers were used as uncivilized props, or as Great Uncle Henry describes, “walking background.” Banua-Simon’s great grandfather, Anthony, appeared in one of these films: Lois Weber’s “White Heat” (1934), which was the first Hollywood movie shot in Kaua’i. “The title ‘Cane Fire’ is the unofficial title of Lois Weber’s ‘White Heat,’ the lost plantation-based melodrama that’s considered Kauaʻi’s first Hollywood production,” Banua-Simon shares. “I was drawn to the fact that among other things, the climax where a character deliberately starts an out of control cane fire was censored to discourage a potential labor revolt.”

Though censorship prevented “White Heat” (1934) from being released, Banua-Simon and Vass weaponize its absence in their favor. By reusing other Kaua’i clips, they recreate the climatic labor revolt in “White Heat” with politicized inflections: rather than a fear of the untamed, their version of the cane fire invokes noble anger and foreseeable change. “I think it works because it’s a sudden eruption of emotion that has been building up for the whole film,” shares Vass. “But it’s kind of abstract and poetic so it can be both powerful and ambiguous – simultaneously a cry of rage and despair, a fantasy of revolt and revenge, a portrait of the island coming apart at the seams.”

As “Cane Fire” shows us, the belief that settler-colonialism is of the past is unconvincing when Native Hawaiians have long been, and continue to be, displaced by Western commercial interest. And, too, there is a shared historical entanglement with imported Asian laborers, through which Kaua’i emerges as another image entirely: a site of political struggle for Native Hawaiians and displaced Asian laborers, not a tropical island to quell one’s fantasies of escape. In these moments of critical witness, where our engagement moves beyond our spectatorship, images held in the archive reveal themselves as not distant catches of the past, but rather glimpses into an honest present. We can see, or perhaps begin to see, how the relationship between the past and the present, between generations of ancestral lineages, isn’t far or forgotten, but painfully close. And when we finally do imagine a life beyond mere survival, together, there is something about a cane fire that feels a lot less fiction, and a lot more lived: right here, in the spirit of the people.

“Cane Fire” screens at the 44th Asian American International Film Festival. Ticket and screening information can be found here.

A previous version of this article mislabelled Anthony as Banua-Simon’s great great grandfather. Additional grammatical corrections have also been made.