Written By: Kano Umezaki

In my last article, I wrote about the political necessity of the PBS “Asian American” docuseries in reclaiming our political-cultural beginnings. But in this article, I want to focus on the series’ limitations as invoked through our (un)shared histories as upholders of U.S. settler-colonialism. Because history shows: our equivocal calls for “resistance” can stem from a desire for settler reoccupation.

The docuseries portrays Asian American history as an ongoing political momentum but simultaneously implicates our (non-Black) roles as settlers on expropriated Indigenous lands. Episode three, “Good Americans,” shows Asian politicians –– most of whom were cis East Asian men –– populating the political scene in Hawai’i. Asians eventually won the vote to turn occupied Hawai’i into statehood, completely disregarding Native Hawaiians’ self-determined demands for independence.

This historical marker necessitates us to understand: Asian politicians entering the U.S. political scene and marking their visibility is not “progressive” or “revolutionary”; it’s violent liberalism. As we’ve seen with Asian political figures such as Elaine Chou, Andrew Yang, as well as with the latest interim ICE director, Tony Pham, the celebration of liberal political “representation” dangerously propels the faux-utopian fantasy that settler states can eventually “evolve” into multicultural nations.

The violence of celebrating liberalism also extends to U.S. congresswoman, Patsy Mink, who was the first racialized woman in Congress. As an advocate for gender and racial equality in court, Mink is regarded as a pathbreaking icon, paving the way for women of color in politics. But we must adamantly remind ourselves: Mink was an advocate for Hawaiian statehood as well –– the very policy which expanded the reach of U.S. settler colonial powers on the island. So we must hold onto the memory that U.S. politicians, no matter what the shifting terms of their racial and gendered identity is, are paid to uphold the violent borders and boundaries defined by U.S. law.

As much as Mink showed bravery in entering the patriarchal grounds of U.S. politics, we shouldn’t place hope or guidance in any U.S. politician when we speak and act of liberation –– which necessitates the complete abolition of the anti-Black carceral state, demilitarization of all imperialist bases (including existing nuclear testing and extraction sites), elimination of debt-producing global monetary corporations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank, and decolonization, which is the incommensurable demand for the complete repatriation of Indigenous lands and the abolition of property. We must, instead, place faith in community leaders and organizers –– particularly BIPOC women, trans, and gender non-conforming peoples –– who have and continue to provide material and educational aid to communities in need.

Since statehood, Hawai’i has become a hotbed for tourism, sex trafficking and military basing –– all produced and proliferated by U.S. neo-colonialism. Though the docuseries makes explicit our (non-Black) roles as beneficiaries of settler-colonialism, it doesn’t show the brutal racial and gendered effects. To briefly phrase it (in words that necessitate expanding): the series omits Native women in Hawai’i being regarded as expendable property by tourists/colonizers/haole who force them into the sex-tourist industry.

Tourist advertisements also grossly depict Hawai’i as a land for “selling” and “occupying” and use Native women’s bodies (and its promise of availability) to draw in colonizer-tourists. As feminist-scholar-activist Haunani-Kay Trask states: “Thus, Hawai’i, like a lovely woman, is there for the taking.” So as we speak and redefine what Asian America not only is but must be, we must also speak of the violence we enact when we side with liberalism as it’s wedded with the settler-colonial enterprise.

We further witness the effects of Asian settler-colonialism in episode four, “Generation Rising,” through images and oral testaments of Korean settler-immigrants/settler-refugees displacing Black neighborhoods in Los Angeles –– a tension which escalated during the 1992 L.A. riots. The media fed the fuel between Korean and Black communities, pitting the colonized against each other in an attempt to save the face of American meritocracy. But despite media exacerbations, it’s true that (non-Black) Koreans –– as well as the Asian diaspora more generally –– and their/our claims to private property help reproduce America’s monopoly on the criminalization and incarceration of the materially impoverished. As we remember Latasha Harlins, a 15-year-old Black girl who was murdered by a Korean proprietress, we also remember that certain Asian Americans mobilized in support of the proprietress, showing how our community(ies) have prioritized property and capital over Black humanity.

The anti-Black mobilizations proves ironic when faced with the murder of Vincent Chin. And this irony beckons us to understand how orientalism and anti-Blackness are not contradictory ideologies, but rather complementary facets of white supremacy. From incarcerating Japanese Americans in the 1940s, to currently incarcerating and deporting Southeast Asian refugees, our histories invoke how the incarceration of orientalized peoples has a direct, constitutive relationship with the anti-Black carceral state. Therefore, when we speak and act in response to “anti-Asian” racism –– as recently made more visible under rising Sinophobia brought by U.S. imperialism across the trans-Pacific –– we must also speak and act in response to its constitutive relationship with anti-Blackness.

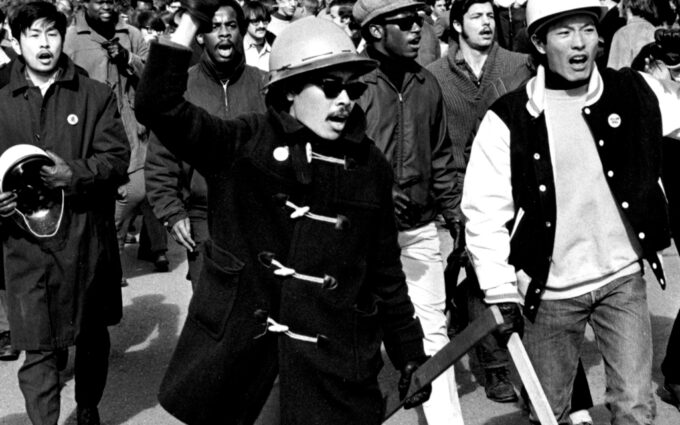

While watching the docuseries, we can begin to chart what Asian American resistance can be when not tied and co-opted by desires for settler reoccupation. We see Asian American youth rise in solidarity with the Black-led Third World Liberation Front and its demands for Third World studies at San Francisco State University. Filipino farm-workers start grape-strikes against their growers. Chinese laundrymen publish poetry in journals meant to establish communities outside of colonial surveillance. Undocumented Asians contest the abstractions of U.S. citizenship. In other words, despite our political marking as “perpetual aliens” in which we remain unassimilable, incomprehensible and illegible to the Western imperialist imagination, we come from lineages where we have always been legible to us, by us, and for us.

And this act of witnessing each other, in what I call communal legibility, is what necessitates and reproduces sites of belonging(s). Because we as a community know: we have survived and loved through witnessing in and from each other. We have built through recognizing each other’s presence, visibility and legibility. We don’t need a country to love us to prove ourselves worthy of a story or a living.

While America has anxiously abstracted our (un)shared histories and institutionalized us as “knowable” objects, “Asian Americans” makes an ambitious –– though unfinished –– attempt at restoring our history into memory. As an educational initiative, the series helps Asian Americans reconcile with our historical (dis)belongings to America, but it does not do so through a transnational, anti-imperialist lens. The series briefly makes visible images and testaments of U.S. and Japanese imperialism in Korea, Vietnam, Philippines and more, yet, by the end, beckons viewers to find reconciliation in searching for acceptance into the United States.

Perhaps this is the greatest shortcoming of the docuseries: its lack of analysis from a materialist lens. The series offers little critique of U.S. imperialism across the trans-Pacific and its connection with domesticated orientalism. Nor does it make the connection between the global sexual violence of feminized Asian people and the consolidation of ongoing Cold War politics. Or the relationship between Sinophobia and the militarization of the Pacific. So as much as the docuseries shows, it also equally omits what has already been silenced from us.

“Asian Americans” begins to retell our shared and respective histories, but it still caters to making us “legible” to white acceptance. It’s possible the series went through censoring because of its affiliation with PBS, because oftentimes, films funded through the corporate non-profit relationship are obligated to represent a sanctioned, liberal Asian American identity. This often means policing communal rage and resentment into articulated grievances, or confronting trauma with a forced hope of one day being accepted into the settler-state. Regardless, the docuseries takes a step forward towards dismantling the Western imaginary, but there is still so much more to go. There is so much left to remember.

“Asian Americans” is available to stream online and on your local PBS station.