Written By: Kyubin Kim

This article may contain spoilers.

Since her childhood growing up in Taiwan under martial law, director Mian-Mian Lu has been pushing conventional boundaries. In high school, Lu started a drama club and directed her first feminist play about vaginas entitled “Are you a virgin?” In college, Lu majored in Chinese opera theory. In 2008, Lu packed up and moved to New York to live like an “old romantic artist” before returning to Taiwan for film school. Lu’s career trajectory transgresses nations and art forms, and I was thrilled to speak with Lu about her feature directorial debut, “Mickey on the Road.”

Lu began writing her Taiwanese road trip film “Mickey on the Road” in 2011. In the film, two best friends, Mickey (Pao-Wen Yeh) and Gin Gin (Ya-Ling Chang), travel from Taiwan to Guangzhou, China in order to search for answers from the people they love. Exhausted by the homogeneity of women in Taiwanese movies, Lu pointed out, “The female characters, they’re either uniform, very innocent, very cute … It’s just ridiculous. They’re not evil, they’re not dangerous, they don’t swear, they don’t do bad things. They’re like perfect dolls … I wanted to have a strong female character.” As a female viewer, Lu was inspired to direct films that actually reminded her of the women in her life: “When I was growing up, all my best friends were not like that. They’re on the street, they’re fierce. I want to speak for a different kind of woman.”

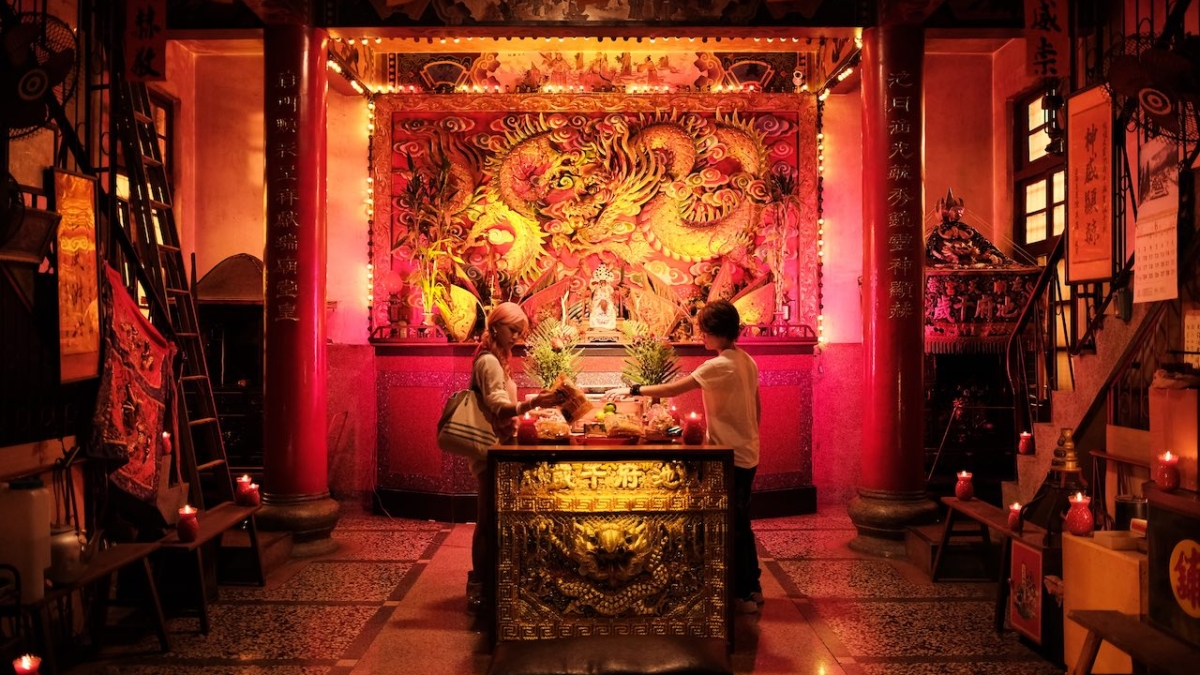

Perhaps that’s why the film starts off so confidently with what film theorist Laura Mulvey would describe “the female gaze,” with the woman as maker, not bearer, of meaning. The film opens with two women peering into a glass-enclosed temple miniature. Temple parade performer Mickey is dressed in all black with a short, androgynous haircut, and foiled against her is pink-haired Gin Gin, who is dressed in all pink.

The film makes a point to further distinguish the two characters’ individualities. In the first sequence, Mickey practices martial arts in sharp, punchy strokes. The camera tracks her muscular body movements and rests on her unflinching face. The camera then cuts to pink-haired gogo dancer Gin Gin, dancing on a pole with a lit up temple in the background. Gin Gin’s movements are high energy and fierce, ultra feminine and strong.

While Lu portrays the different strengths present in these two women, she also focuses on the chemistry of female friendships we rarely get to see on screen. Mickey and Gin Gin are street smart women who take care of each other. They kick arcade machines to scavenge for coins, stuff mailboxes with flyers and ride a motorcycle screaming, “You fucking loser!”

When Mickey is practicing in an all-male temple parade troupe, her teacher yells at her when she makes a mistake, “Women are prohibited to perform!” As Gin Gin challenges why, the man answers, “Because women aren’t clean and that’s the rule!” Defending her friend, Gin Gin yells back, “We are clean!” Lu explained this protective dynamic further, “When you’re with your best friend, it’s like family. You see a lot of men in action movies but I want to show that women also have that kind of connection too.”

What bonds the two women in the film beyond their friendship are their individual journeys to leave home. Lu was inspired most by the temple parade, a major activity in rural and major cities. In Taiwan, the number of temples outnumber convenience stores, and during parades, tens of thousands of people follow a route to protect and bless people. In the film, Mickey is heavily involved as a temple performer and Lu explained, “I know kids who grew up in a broken family, and I know kids who gain confidence who perform in those temple parades because that’s the only stage they can stand on.”

The two characters’ respective missions, Mickey to find her absent father and Gin Gin to find her elusive boyfriend, mimic this temple parade route. For Lu, this idea of agency was important. These two women raise the question of what they are searching for by themselves, look for the answers by themselves, and come back to deal with the same hardships they tried to escape. Like many road trip films where the travelers return as changed people, the characters’ transformations are personal and must be undergone on their own.

“Mickey on the Road” may have been a road film but Lu liberally expands the realism typically associated with the genre by creating a magical surrealist feel in the story. In one dream sequence, Mickey is licking honey from a glass wall with a dragon sweeping behind her. In the last scene of the stabbing of her father, Mickey’s punches are interlaced with her temple performance practice. Lu remembered discussing the scene with her editor Chen-Ching Lei who wanted to chop the stabbing scene in a novel, unexpected way. “To add martial arts [into] these imaginary scenes,” Lu said, “it’s more real to the character.”

Lu’s ethos as a filmmaker are equally limitless and anti-monolithic. She doesn’t necessarily hope all her viewers will receive one definitive conclusion upon watching her film but hopes that as a filmmaker, “You want to have an echo. It’s like standing in a valley and holding in a shout, and then you shout it. And you hope that someone at the other end of the valley will reply or echo your voice … I want to connect to people who feel lonely, who struggle, and somehow this movie can give them this feeling of being connected.”

“Mickey on the Road” certainly builds layers of connections for the audience. In my conversation with Mian-Mian Lu, I felt connected hearing her confidence in knowing what stories must be told. Lu bluntly points out that there are so many voices, especially marginalized ones, that are too often buried under the same conventional narratives. She recounted, “My advisor in film school asked, ‘Mian Mian why do you always write feminist movies?’ I was like ‘I’m a woman right, should I deny this fact?’”

The first time director Mian-Mian Lu watched “Wonder Woman,” she burst into tears of joy. “After so many years we finally have a superhero. She saves the world,” Lu remembered celebrating. Mickey and Gin Gin may not be classic, conventional superheroes, but this film celebrates the ferocity of female characters and female artistic visions in a way that is just as empowering, uncompromising and brave.

“Mickey on the Road” makes its East Coast premiere at the 44th Asian American International Film Festival. Ticket and screening information can be found here.