As if staging dramatic scenes under the sea weren’t arduous enough, Abaya wanted to shoot her next film in a war zone.

The war in Mindanao had erupted in the early 1970’s during the Marcos era. It was still ongoing some thirty years later, costing some 120,000 lives and precipitating massive displacements and evacuations. 82 Mindanao, in the south bordering Malaysia and Indonesia, is one of the country’s three geographical regions; one of the biggest islands in the world, larger than the Netherlands, Austria, or Portugal; the most religiously, culturally and ethnically diverse part of the country. It is the promised land, the country’s bread basket, home of the pioneers, the richest, the poorest, the most colorful, the most violent, the place that your grandmother told you never to visit, the enigma.

Whereas the Spaniards managed to Christianize the other two regions, they failed to do this with Mindanao. So fierce was the resistance from its native Muslim population, the colonizers were only able to hold together some far-flung garrison towns and outposts, and mostly left the region alone. The American administration passed a law in 1919 invalidating the legality of vast areas of inherited property of indigenous inhabitants and granted itself the authority to confer land ownership in Mindanao, which left many Muslim and indigenous inhabitants landless.

Later American and Philippine administrations promoted heavy migration by Christians from other parts of the Philippines such that parts of the region are now an inextricable mix of Muslim, Catholic, Protestant, and animist groups and cultures. Undeniably the richest region in terms of cultural diversity and natural resources, it also has some of the most poverty-stricken provinces, abetted by long-time neglect from the national government. It has convulsed throughout its history in violent clan wars arising from a brew of land right controversies, questions of fair distribution of resources, a warlord system still in place, fanaticism, fear, and mistrust. Paradoxically, it is the very intractability of its problems that has largely preserved the region’s natural resources and enigma.

By the turn of the millennium, Filipinos who were living in the other regions had become apathetic to the war. With Bagong Buwan/New Moon (2001), Abaya wanted to show that the suffering of civilians in the war remained real and urgent.

(A decade on, the war has not ended. A framework agreement signed in late 2012 by the Aquino administration and the insurgent Moro Islamic Liberation Front is currently regarded as the best chance to end hostilities.)

Star Cinema, the giant competitor of GMA, signed on for the expensive project, the first film to seriously focus on the war in Mindanao. Abaya as usual made painstaking preparations and sought to learn how to pray and live as a Mindanao Muslim. She frequented mosques, consulted with Muslim scholars and historians, pored over the Bible and the Koran, spent time at evacuation centers, interviewed rebels and government soldiers, and walked around in the war zone. 83

In search of authenticity, Abaya chose to shoot in the areas of conflict, in rural Bukidnon and Marawi City. As if shooting in a war zone weren’t perilous enough, then President Joseph Estrada declared an all-out war against the Muslim insurgents while Abaya and her crew were in the middle of shooting, adding to their peril.

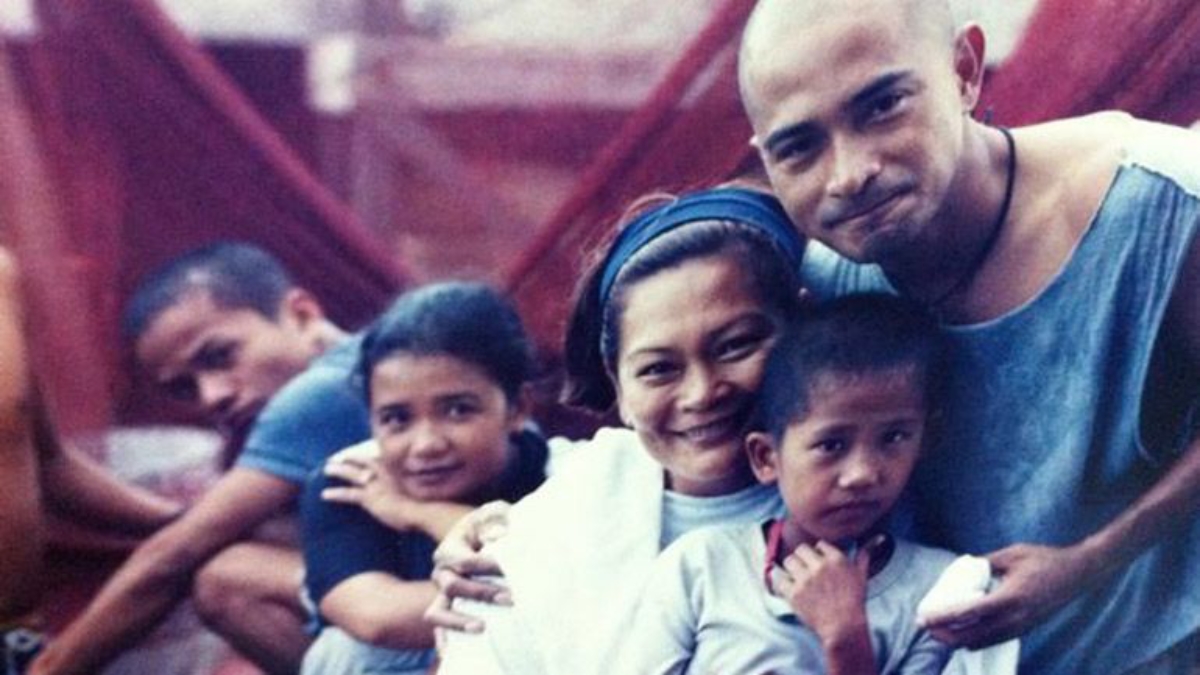

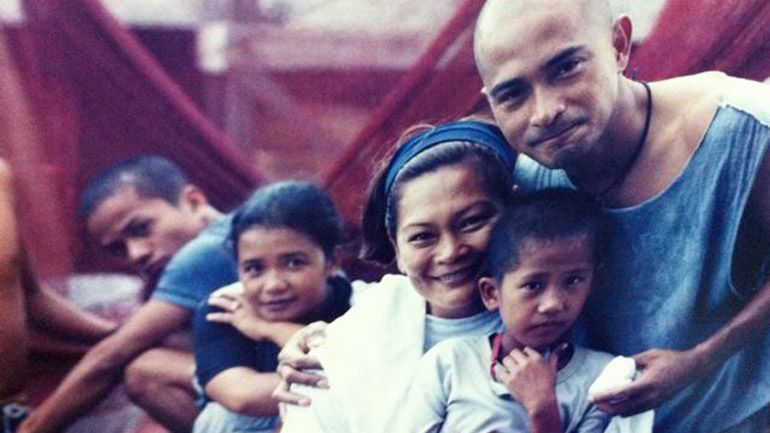

Cesar Montano plays the film’s main protagonist, Ahmad, a Muslim medical doctor in Manila who is called back to Mindanao after his son is killed by a stray bullet during a Christian vigilante raid on their village. Ahmad who desires a peaceful life, wants to bring his wife Fatima (Amy Austria) and mother Bae Farida (Caridad Sanchez) to safety in Manila. But his mother wants to remain where she grew up and his wife wants to stay where her son was buried. Ahmad’s brother Musa (Nonie Buencamino) is a militant separatist and he has heated arguments with Ahmad about peace and war. Ahmad, still a pacifist despite his son’s death, wants to take Musa’s son Rashid (Carlo Aquino) to Manila where he can study, but Musa would rather train him in the fight against the military.

We next see Musa and Rashid in the city where they plant a bomb that explodes among unsuspecting vendors. A Christian boy from Manila, Francis (Jiro Manio), happens to be around and the ensuing mayhem gets him separated from his parents as he takes refuge in a fleeing jeepney that’s also carrying Rashid. For some reason, Francis follows Rashid all the way to the village where Ahmad, his family and the village welcome the Christian boy with open arms.

Already apparent at this point are some of the awkward manipulations of plot and tugging of heart strings that unfortunately marks the rest of the film, as Ahmad’s clan flees from one evacuation place to another and they caught in the clashes between Muslim militants, Christian vigilantes and government soldiers. As if unsure that the audience would ever understand that war is evil and peace is desirable, the characters constantly lament, debate, make speeches about the suffering caused by war, something that the visuals have already pointed out to greater effect, so much so that one may find oneself wanting to cry out to the characters to shut up already.

There’s nothing wrong with starting out with representative types – Ahmad as the peace-loving man who gets pushed over the edge and pulls the trigger; the idealistic soldier (Jericho Rosales) who soon finds himself caught in a real war; the Muslim militant who will not listen to reason; Christian boy Francis who starts out as ignorant and prejudiced only to end up loving and respecting the Muslims. However, they remain types used this way and that to make a point and to represent the “message” of the film, rather than characters allowed to develop into actual people and souls that are relatable and understandable in their own right.

Sure enough, the Muslim teen’s having dropped off the bomb in the city is soon forgotten when the Christian boy cutely follows him back to the village; the Muslim hero saves the Christian soldier; the Christian woman (Jodi Sta. Maria), dying from childbirth, asks the Muslim hero to adopt her son; the Muslim grandmother makes a dying speech to the Christian boy that when he goes back home, he should tell them stories of the Muslims who took care of him; the Muslim hero dies while trying to save the Christian boy. It’s so hard to find something not calculated to push the message that when a character sprains her ankle, it’s almost a relief to encounter something natural.

Despite the handicaps, Montano turns in a quiet, unsentimental performance; and so with some of the other actors. As always with an Abaya film, the meticulous preparation in production design pays off in the rich visual texture of the film (though the evacuees’ costumes seem miraculously spotless throughout). Photography (by Totoy Jacinto) justifies shooting in the area. There is obviously an earnest and noble purpose here, that of driving home the reality of war and the suffering it causes; and one must not forget that Abaya faced danger in shooting the film. But unfortunately, mere earnestness and nobility of purpose does not a credible film make. And in this film, authentic glimpses and insights come few and far between, difficult to come by in the films manipulative muddle.

The film got mixed reviews, and for the first time, an Abaya epic was pretty much absent from that year’s Manunuri nominations, except for the well-deserved inclusion of Montano and the film’s cinematographer. Abaya’s reputation for careful productions, standing out in a commercial industry where slapdash works were rule, and Star Cinema’s powerful publicity machine helped ensure that Bagong Buwan met with box office success. For Abaya, such success happily disproved warnings she had been getting all along, that the majority Christian Filipinos would not be interested in Muslim or “ethnic” stories. 84

After Bagong Buwan, a number of serious indie films shot in Mindanao about some aspect or other of the Mindanao conundrum would follow, some of them by Mindanaoans themselves, in long-due and welcome stirrings of decentralization from the traditional power center of Manila: Arnel Mardoquio’s Paglalakbay ng mga Bituin sa Gabing Madilim/Journey of the Star in the Dark and Hospital Boat, Siegfried Barros-Sanchez’ Tsardyer/Charger, Sheron Dayoc’s Halaw/Ways of the Sea, Gutierrez Mangansakan’s Limbunan/The Bridal Quarter; and Brillante Mendoza’s Sinapupunan/Thy Womb. A number of these films reached greater artistic heights than their forerunner, but none has surpassed its all-encompassing scope or ambition.

Abaya’s three latest films, Jose Rizal, Muro Ami, and Bagong Buwan were now being called a “trilogy of masculinities,” recalling the so-called feminist trilogy earlier in her career. This new “trilogy” had several elements in common. As with the earlier trilogy, Lee wrote (or co-wrote) their screenplays. They all revolve around strong male characters, played by Montano, whose experiences take their consciousness to another level: about nation, sea, peace and war. They all lose their lives (and lose their only children to death as well). Abaya said of this stage of her career: “Without deliberate intent, I journeyed from the feminist agenda of social and economic equity to the human quest for peace of mind and spiritual liberation.” 85

She was ready for a change from the masculinities and while searching for a new subject, she thought, why not follow-up on all those characters in her early feminist film, Moral? 86 “Moral 2” would again be written by Lee and eventually titled Noon at Ngayon/Then and Now (2003). The casting was a matter of much speculation in the film community, as three of the four original actresses who portrayed the four main roles, Lorna Tolentino (Joey), Gina Alajar (Kathy) and Sandy Andolong (Sylvia) were still eminently active and viable, one of them, Tolentino still enjoying star status. Perhaps wanting to create a fresh new buzz, Abaya and her producers at Star Cinema opted to completely replace all four actresses, only retaining two actors for the satellite characters, Laurice Guillen (as Joey’s mother Maggie) and Lito Pimentel (as Celso, the lover of Sylvia’s husband).

The film starts with Joey (Dina Bonnevie) arriving back in the Philippines from America where she had been teaching at a primary school. She has come home to be with her mother who is struggling with cancer. The four best friends from UP college days find the reunion as a chance to share their problems with each other.

Sylvia (Eula Valdes), who is now assistant dean at a school, is still in love with her ex-husband Robert (Nonie Buencamino) but she has already accepted his relationship wtih his long-time lover Celso (Pimentel), breaking out into hysterical giggles when she goes out with the loving couple. She wants their son Bobby (Marvin Agustin) and his wife Miriam (Dimples Romana) to give her a grandchild but she has been frustrated so far, suspecting that her daughter-in-law is sterile.

Maritess (Cherry Pie Picache) is now a single mother, with an unspecified number of children living in Canada. The three children still around are giving her problems: Bryan (Paolo Contis) is gay and she can’t accept this; the pregnant Guia (Jodi Sta. Maria) wants to stand on her own and refuses to marry her baby’s nice father Mike (Patrick Garcia); and Levi (Jericho Rosales) is a moody sculptor without direction in life.

The flamboyant Kathy (Jean Garcia) has given up on her singing ambitions and is now into New Age mumbo jumbo and foreign boyfriends. Her husband having left her, she is single mother to Bernadette (Aiza Marquez) who dresses and acts as annoyingly as her. Bernadette is hopelessly obsessed with Maritess’ son Bryan but he has the hots only for closeted gay man Archie (Lorenz Martinez), a Congressman’s son.

It’s a lot of characters to keep juggling around and amazingly, Lee and Abaya manage to keep all their stories spinning clearly and distinctly. It’s supposed to be a light comedy with something to say about contemporary morals, but the film’s schmaltziness makes one begin to wonder why the Laurice Guillen character is not dying of diabetes instead of cancer. An early portent is a song and dance to welcome Joey performed by pretty much all of the above in a conga line about how they all couldn’t help but notice her smile. Overshooting for laughter and tears, the syrup is laid on as both Bryan and Celso exaggerate their gay swishiness, Kathy and Bernadette overplay their flamboyance, and the four dear friends swoon and coo, this affliction apparently contagious to their kids as well.

There’s also much spoon-feeding, with such blatantly direct lines of dialogue like, “Your principles or your feelings? What is more important?”… “You’re in my heart and I can’t erase you”… “My philosophy is, wherever you can find love, take it, so long as you don’t hurt others”… “From now on we will make love not because we want to have children or mother orders it, but because we want to.”

Variety couldn’t help making a dig not only at the film but at the Filipino penchant for attention-getting nicknames: “As expected from an item featuring thesps like Dimples Romana and Cherry Pie Picache, Noon at Ngayon has a serious case of the cutes. Loosely following vet helmer Marilou Diaz-Abaya’s 1980’s use of same characters, new pic reps a reunion for quartet of fem friends, now pushing middle age and dealing with the problems of kids and ailing parents. Soap cycle consists of fights followed by teary resolutions and giddy laughter, endlessly repeated and all set to tinkly synthesizer music.” 87

In a film that wants to be so generous and part of whose theme is about the need for acceptance, there are arresting lines of dialog and touches that momentarily escapes from the general giddiness. When Levi stops the terminally ill Maggie from toasting him with a swig of beer, she retorts: “Here I am, dying, and you want to stop me from living?” (Sounds more fleet-footed in the original Tagalog: “Namamatay na nga ako, pagbabawalan mo pa ‘kong mabuhay?”) Or the scene of the Congressman’s wife, the mother of Bryan’s gay boyfriend, talking bluntly and flamboyantly, but only behind closed doors, about her son’s gayness. Or there’s Guia reading her baby to sleep, and the book is Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Though the actors are visibly and gamely trying to do their damnedest best to turn in a good job, and almost all do have occasional affecting moments, only a few manage to deliver consistently credible performances. The veteran actress and director Laurice Guillen invests her role as the dying Maggie with an unfussy dignity, successfully embodying the film’s message of accepting one’s fate with grace. Despite the temptations that so many others in the cast succumb to, she never overplays to the camera; she seems to be always coming from within and remains credible even when having to mouth embarrassing lines of dialogue. And there’s Jericho Rosales as the young Levi who finds himself falling in love with Joey (a believably attractive Dina Bonnevie) who could be his mother. He delivers such a consistently graceful, heartfelt, and nuanced performance, it’s like watching someone walk on water while everyone around him is floundering and in danger of drowning. No wonder even as the Manunuri totally shut out the film from any nomination for the year, they made an exception for Rosales.

Abaya reflected on her consciousness as a woman and what she sought to transmit with Noon: “In a sense, I am just coming full cycle to what concerns me as a person. It necessarily departs from my concerns as a very impatient, angry woman during the Martial Law regime and the Ninoy Aquino assassination and goes back to my concerns as a woman in search of peace not only in Mindanao but peace of mind and heart.” 88

Her effort to depict the search for peace in Mindanao had deeply affected her. She was haunted by the Muslim women whom she met in the course of making the film. Abaya said: “I owe a debt of gratitude to our Muslim sisters for their hospitality in receiving me, a Roman Catholic, with warm hospitality, entrusting me with their deepest personal experiences.” She was humbled by “their courage in battlefields and their generosity in evacuation camps. From them I rediscovered the value of faith, and in studying Islam, the Roman Catholic religion was re-enkindled in me.” 89

Feeling guilty about leaving her Muslim sisters after wrapping up on Bagong Buwan, she volunteered with the the Mindanano-based Silsilah Peace Institute, a dialogue movement that trained workers on the skills of promoting deeper understanding and better relations between Muslims and Christians, and those of other living faiths in Mindanao. (Silsilah is an Arabic word that means “chain” or “link.”) Abaya was tasked to head Silsilah’s media department and for its 20th anniversary, she wrote and directed the hour-long documentary Silsilah: Dialogue Movement for God’s Peace (2004). 90

As with Abaya’s more known feature films, craftsmanship distinguishes the documentary from the start, with a shot that swoops in acrobatically from majestic mountains to the humble stones that litter an unpaved path. The film, narrated by Abaya in a tone as gentle as a whisper, follows the activities of the founder of the movement, the Italian-born priest Father Sebastiano d’Ambra; its Muslim editor of publications, McCormick Dinggi; and various volunteers of the movement as they train, pray, share stories of past griefs, and visit the mixed communities of Zamboanga. Their humble, sober dialogues with each other and their attempts to find what’s admirable in each other’s religion and culture could arouse hope even in a jaded skeptic that indeed a lasting peace between Muslims and Christians is possible.

The documentary goes into the roots of the decades-long Mindanao war, from the successful Muslim resistance of the Spanish colonizers, of which all Filipinos, Christian and Muslim, take national pride. The film recalls those fateful years in the 1970’s when the war began, the separatist MNLF on one side and the Martial Law government troops on the other and how it has damaged everyone living in the area, psychologically, socially and economically. The documentary reminds us that there can be no peace without justice but it also focuses on those people who have found strength in their religion to accept what they could not change in their lives. Riveting is the story by a Christian woman who moved to her husband’s native Mindanao, how her husband got killed in a crossfire as he tried to harvest copra in a no man’s land, and how it was a Muslim man who volunteered at great peril to retrieve his bloated body for her.

Moving too are scenes showing people in a poor Muslim community welcoming Father d’Ambra, Muslims and Christians praying together, and the resolute faces briefly glimpsed of ordinary people living in the war zone.

In her narration, Abaya shares her view of dialogue as both a pilgrimage and an adventure with other human beings, the world of creation, and God. She believes that this dialogue can open one’s eyes to surprising moments of beauty, examples of which are captured in her film. Even the staunchest atheist might be moved by the kind of religion, Christian and Muslim, that is evident in Abaya’s film and her serenely passionate narration: Non-judgmental, humble, and generous.

Abaya’s efforts with Silsilah and her film Bagong Buwan brought her to the attention of peace volunteers abroad and she became part of the PeaceWomen Across the Globe, an international network of 1,000 women that was nominated for the 2005 Nobel Peace Prize. 91

The religious inspiration that Abaya found through her Muslim sisters also got her more involved with Catholic groups closer to home. One day, she received a call from Father Pablo David, brother of Randy David who hosted her former TV show Public Forum. Abaya recalled how in a “painfully shy” voice, the priest told her that a new cable station had offered them a spot and could he seek her advice. That was how she began to travel regularly to the AMANU media center in Pampanga to teach TV production to the seminarians, organize a media bureau, and direct Men of Light, a weekly talk show on the scriptures, that was eventually broadcast by some 70 cable stations in the country. 92

A film instructor at the Ateneo de Manila for almost three decades, she was never far away from the company of the Jesuits and, her Ignatian devotion rekindled, she became more active in her role as trustee and advisor of the Jesuit Communications Foundation, the Society’s media arm in its Philippine province. Abaya directed her next feature-length film, a TV movie, for them.

One can’t help but be wary of a film that at its inception is made with some advocacy or agenda in mind, in this case, to promote priesthood vocation. How often have we seen agenda-driven films — religious, feminist, pacifist, political — capsizing on the treacherous rocks and sandbanks of forced messages, manipulative plot, cardboard personalities, polemical dialogue, and mouthpiece characters?

Maging Akin Muli/Be Mine Again (2005) with a script that Abaya wrote, begins with the ordination to deaconship of young seminarian Jun Jun Santos (Marvin Agustin). As an ordained deacon, he will need to apprentice for at least six months with a parish priest who has the power to recommend him to the priesthood or raise objections.

The film follows the difficulties and insecurities that the deacon goes through in his apprenticeship. The elderly parish priest Father Doy (Noel Trinidad), under whom Jun is assigned, is a conservative and flinty character who reprehends him for sporting an earring, having a puka shell next to the cross on his necklace, checking on a text message in the middle of mass, messing up an important wedding ceremony after a woman runs out crying, and returning an envelope with monetary donation to a poor family.

Dolly (Missy Maramara), a childhood sweetheart of Jun’s, constantly sends him text messages. Jun was only supposed to attend the seminary for education but ended up wanting to be a priest. Dolly obsessively wants to resurrect their relationship and blames Jun for destroying her life.

There is Jun’s prison visit to former parishioner Nonoy (Ronnie Lazaro) who had killed and robbed his employer and is condemned to die. In a powerful and delicately staged scene, Nonoy lays bare his remorse and fears to Jun who can give back nothing but compassion. Jun’s helplessness at Nonoy’s eventual death brings him a crisis of faith.

The film depicts priests and would-be priests (Father Doy, Jun’s seminary mentor, Jun himself) as flawed human beings. Though they can never have perfect vocations, they can only aim at perfect surrender to their calling. In a powerful scene where Jun addresses the parishioners from the pulpit, he apologizes to them: “I know you were expecting light from me, not muddle. I thought I knew a lot but now I realize that I know nothing except my passion to serve God as a priest despite my stumbles and shortcomings. I don’t know if God is mocking me but whenever I try to be like Superman, I fall down in the middle of real people… like you, bruised with the suffering and the trials of life.”

Much of the film is set in the old stone churches that Abaya loves and has featured so prominently in her movies, starting with the first. With Mo Zee’s cinematography, the film caresses the frescoes, icons, candles, altars, incense burners, songs, and faces found inside a church. Abaya stages three well-integrated masses in the film, and in simple and direct manner, she manages to express the sense of grandeur and depth underlying a Catholic mass that on normal occasions can be so prosaic and downright boring.

This modest, little-seen work started as an advocacy film but ended up being a legitimate feature film in its own right, among the best in Abaya’s filmography. Watching Abaya’s handling of her cast, led by an engagingly relatable and credible Agustin, sometimes seems like witnessing someone walk on a tightrope. Emotional scenes sometimes flirt with gravity and sentimentality, but you find the artist always knowing when to pull back and maintain her balance. The style of the film can’t be more simple, in the manner of late works by some masters. Gone is the sense of a director wanting to please producers, impress critics, excite the masses. Freed from the earthly coils of big budgets and big expectations, there is here only the sense of someone sharing, without ambition or calculation, simply and directly from the heart.

The voyage had certainly been a long one from the time that Abaya first started directing her fervid feminist films, sure about social, political, economic solutions just around the corner. Now in her middle age, she had encountered human situations that even the best will in the world could not solve, and she sought in her later films to capture the grace of acceptance. In 2007, Abaya was diagnosed with breast cancer. It surely did not escape her that she herself had a dry run on this very same affliction as she guided Laurice Guillen depict a breast cancer sufferer struggling to accept the ravages of body and soul. When the illness forced Abaya to scale back with her film work, her father suggested that she set up a film school in a lot the family owned, so that Abaya could still continue working, doing what she liked best, teaching. 93

Her passion for teaching came to her earlier than film. Abaya recalled: “I have always loved studying and teaching. As young as eight, I would gather my siblings and house help, mount a green blackboard in front of them, and with real chalk, mark important details of lessons I learned in class earlier in the day. I always tell my students to learn as much as they can, then give everything away to anybody interested. This way, they’ll always have room to learn even more.” 94

She had been teaching film since 1981, just a year after she directed her first film. Among the students in her very first class at Ateneo was Jeffrey Jeturian who would go on to an internationally awarded career as director. Other students of Abaya’s have distinguished themselves as production designers (Judy Lou de Pio, Cris Silva), editors (Manet Dayrit, Tara Illenberger), screenwriters (Chris Vallez, Gino Santos) and cinematographers (Mo Zee, son David Abaya). 95

Her roster of students either at her institute, the Ateneo, the Asia Pacific Film Insitute, on the set, or in private sessions at her home, include film directors extremely diverse in sensibility, age, and aspiration, ranging from the most blatantly commercial to the most esoterically experimental and a lot in between: Olivia Lamasan, Sherad Sanchez, Jun Lana, Quark Henares, Jerry Sineneng, Tara Illengerger, Mike Tuviera, Rory Quintos, Marie Jamora, Lisa Yuchengco, and Gino Santos. 96 97

Santos, who studied under Abaya at both the Asia Pacific and Diaz-Abaya institutes, recalled that Abaya was firm with her students and made sure that they were always doing work in terms of fixing details of the set and helping out in tasks. He said she was “very motherly” and had a predilection for calling her students “anak” (son or daughter). 98

Abaya kept a simple principle for choosing and developing a project: “One of my first considerations is necessarily the material of the subject itself, which is to say who is this film about? Can I fall in love with this who, can I care enough about this who? If that attracts me, then I move on to with whom am I going to make these films? And if I muster enough confidence and trust in the people I will (be working) with in this film, only then do I really proceed… with what would I like to know about this who in my film?” 99

There’s a trace of Abaya’s feminist beginnings, as well as the Filipino penchant for acronyms, in a principle of filmmaking that Abaya taught her students, in this recollection by documentary director and journalist Lisa Yuchengco: “Marilou always emphasized that it is important to express the significant human experience (SHE) in any storytelling. Every story is about love and how that love transforms us. How many hearts and minds were touched by your story? Winning awards and trophies are good, but more importantly, will your films be remembered and will they have any significance to the future generations? She also stressed the importance of generosity, in sharing what you know to help and empower audiences.” 100

Abaya being celebrity, the press and TV covered the progress of her diagnoses, therapies, remissions, relapses. She took this as an opportunity to share insights on what the illness was teaching her, in various TV and press interviews that she always tried to leaven with humor even when she was talking about how she had already ordered her white dress for the casket. Once, she shared her original reaction when she learned of her illness: “The first thing that entered my mind was… oh my God… THANK YOU… I have time! Because I was thinking you could go down the elevator and it could drop and you wouldn’t have had time to think about the people whom you love, how they still need you, and how to prepare for the inevitable which is death.” 101

In 2009, her cancer went in remission and she seized the opportunity to direct another feature film that she was writing, Ikaw ang Pag-Ibig/You Are Love (2011). It was produced by her film institute and the Archdiocese of Nueva Caceres to commemorate the tercentenary of Our Lady of Peñafrancia in Naga, an object of veneration and pilgrimage since it was enshrined there three centuries ago. Her son David was cinematographer. The film took over two years to finish, at which time Abaya experienced a remission, a recurrence, and another remission. 102

The film concerns an editor (Ina Feleo) working on a documentary on the tercentenary of the Virgin and how she and her dysfunctional family are forced to grapple with illness and questions of faith and mortality when her brother, a young priest (Marvin Agustin) is stricken with acute leukemia. 103 104

Star Cinema opened the film simultaneously in 100 theaters nationwide and the film toured schools and universities. 105 In an echo of Abaya’s former wars, reviews were divided but almost all noted Abaya’s hallmark of craftsmanship.

Ikaw ang Pag-Ibig is the only one of Abaya’s 21 theatrical films that this author has not seen, thus the muse forfends him from excreting any more of his useless and irrelevant comments. Instead, let us visit writer Richard Bolisay’s eloquent words on the film and its creator: “Cancer didn’t stop her… It was a very emotional time, but she managed to shoot and finish Ikaw ang Pag-ibig, which would turn out to be her last hurrah. A tribute to Our Lady of Peñafrancia, the film is a farewell and love letter to a generation she is about to leave behind, a piece of work that understandably shows her frailness. Like most of us, she was living and dying at the same time, and in those two hours came her final breaths in her homeland, submitting to the industry she served for 30 years, cinema being the only homeland of filmmakers who fought their wars until the very end.” 106

Meticulous to the end, Abaya planned and prepared for her four-day vigil and burial, asking the Jesuits to carry them out in order to spare her husband and two sons of the strain. She chose the speakers and contacted them. She specified the bouquets of white blooms. She gave instructions that the ceremonies be simple. She didn’t want the casket in the middle of the Ateneo chapel, but humbly to the side, leaving the center for the altar. 107 108

Said her son Marco, “That was our joke – that she was directing until the end.” 109

She must have looked back on the days when she had no inkling that she would ever be a director. Or the time her mentor Ishmael Bernal said that one should not be afraid to fail. How Bernal would often quote the great director Lamberto Avellana from the First Golden Age say that he may have made awful films, but that in the end, he would be remembered for (film classics) Anak Dalita or Badjao or Portrait of an Artist. 110 Abaya exemplified this maxim of art. She may have had moments of nervousness, but in the end, she was not afraid to fail and thus left behind some of Philippine cinema’s most disappointing failures, disappointing because they were so ambitious, as well as some of its most abiding classics.

Abaya tried to work within the commercial film industry, endeavoring to improve its genre productions from within. She tried to tame the hydra monster through conscientious preparation and craftsmanship, producing films that were always a cut above the norm, displaying greater ambition, better concepts, more carefully staged scenes. In the end, artistic salvation for Philippine cinema came from without, from the Philippine indie movement led by the likes of Lav Diaz and Brillante Mendoza who initiated its Third Golden Age in the mid-2000s, working outside the commercial establishment, quick to seize the digital revolution, agile at capturing reality with guerilla tactics, gritty, tough, authentic, unencumbered by big studio systems and expectations, practicing abnegation for artistic freedom. So much so that movie stars now often regard their work at teleseries and big-budget films as their day job, and look forward to fulfilling their artistic aspirations through almost gratis participation in indies that go on to reap acclaim at international festivals where Philippine independent films are now an admired staple, a far cry from the time when only a few names, Lino Brocka, Mike de Leon, Marilou Diaz-Abaya, reached those distant shores.

The faith that she rediscovered before her illness became refuge and beacon for her. And she breathed God and cinema to the end. Lee made a promise to her that he would realize the project they had been collaborating on for months, a “double memoir” about their life and work during those youthful heady days of the 80’s. Abaya was still working with Lee on scripts for future projects. One of them was for a film biography of the 19th-century Filipino painter Juan Luna, contemporary of Rizal. She bequeathed the project to director Olivia Lamasan. The other was a project left to her by Bernal, about Maria Rosa Henson, the first Filipina to publicly reveal her story as a comfort woman for the Japanese army in World War II. This project Abaya left behind for another female director, Rory Quintos. 111 112

It would just be an “adventure.” That’s how she talked herself into taking on her first job as director over thirty years ago. The adventure lasted a lifetime. With the camera beside her, she reached out and explored the world around her and took a generation of moviegoers along. She left behind for Filipinos fragments of their obsessions and transitions, works that may wax and wane in repute but yet remain, objects of fascination in the dark, tropes and markers for adventures past and adventures still concealed.

References

82 Schiavo-Campo, Judd Mary. The Mindanao Conflict in the Philippines: Roots, Costs, and Potential Peace Dividend. Social Development Papers, World Bank (2005 February), p. 5.

83 PeaceWomen Across the Globe. Marilou Diaz-Abaya (profile). (Bern, undated.) Note: PeaceWomen Across the Globe is an international network of the 1,000 women, that included Abaya, nominated for the 2005 Nobel Peace Prize. http://www.1000peacewomen.org/eng/friedensfrauen_biographien_gefunden.php?WomenID=1160

84 Ibid.

85

86 Diaz-Abaya, Marilou. Women’s Stories and Film’s For Peace: A Filipino Director’s Experience. (National Confederation of Human Rights Organizations, New Delhi, 2006). http://www.nchro.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=2388:womens-stories-and-films-for-peace-a-filipino-film-directors-experience&catid=42:world-peace&Itemid=26

87 Eisner, Ken. Review: Noon at Ngayon. (Variety, 2004, Jan 14).

88 Ibid. 61.

89 Diaz-Abaya, Marilou. Women’s Stories and Film’s For Peace: A Filipino Director’s Experience. National Confederation of Human Rights Organizations (New Delhi, 2006). http://www.nchro.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=2388:womens-stories-and-films-for-peace-a-filipino-film-directors-experience&catid=42:world-peace&Itemid=26

90 Ibid. 82.

91 Ibid. 82.

92 Ibid 24, 91min. in.

93 Ibid 24, 92 min. in.

94 Diaz-Abaya. Marilou Diaz-Abaya Film Institute and Art Center. (Antipolo City, undated) http://www.mdafilm.com/mda_aboutus.php?BlurbID=9

95 Ibid.

96 Ibid.

97 Cruz, Francis Joseph. Diaz-Abaya and the Story of My Cinephilia. (ABS-CBN News, 2012 Oct. 10). http://www.abs-cbnnews.com/lifestyle/10/09/12/diaz-abaya-and-story-my-cinephilia

98 Santos, Gino M. Email intvw by author. (2013, Jul 16).

99 Ibid. 24, 35 min. in.

100 Yuchengco, Lisa. Asian CineVision intvw. (Transmitted to author by Asian CineVision, 2013, Jul 1).

101 Soho, Jessica. TV interview with Marilou Diaz-Abaya. (GMA TV, San Juan City, 2012, Jan 19). 3m in. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WIHY8d2BQtI Note: Abaya spoke in Taglish (combination Tagalog and English) and this is a translation by the author.

102 Carballo, Bibsy. A Gift of Love from Marilou Diaz-Abaya. (Philippine Daily Inquirer, 2011, Sep. 23). http://entertainment.inquirer.net/14929/a-gift-of-love-from-marilou-diaz-abaya

103 Ibid.

104 Dy, Philbert Ortiz. An Extra Layer of Artifice. (Click the City, 2011, Sep 15). http://dev.clickthecity.com/movies/?p=12559

105 Tariman, Pablo. Faith, Love, Time & Marilou Diaz-Abaya. (Philstar, 2011, Sep 20). http://www.philstar.com/entertainment/728591/faith-love-time-marilou-diaz-abaya

106 Bolisay, Richard. Marilou Diaz-Abaya: Impressions. (Lilok Pelikula, 2012, Oct 23). http://lilokpelikula.wordpress.com/2012/10/23/marilou-diaz-abaya-impressions/

107 Cruz, Marinel. Marilou Diaz-Abaya: A director to the very end. (Philippine Daily Inquirer, 2012, Oct 10). http://entertainment.inquirer.net/62496/marilou-diaz-abaya-a-director-to-the-very-end

108 Ranada, Pia. Marilou Diaz-Abaya’s Limitless Horizons. (Rappler, 2012, Oct 13) http://www.rappler.com/entertainment/14109-marilou-diaz-abaya%E2%80%99s-limitless-horizons

109 Ibid. 107.

110 This was a story about Lamberto Avellana that Bernal like to tell and that this author heard from Bernal himself.

111 Reyes, William. Part 1: Director Marilou Diaz-Abaya: The Last PEP Interview. (PEP, 2012, Oct 8). http://philippineexpressionsbookshop.wordpress.com/tag/marilou-diaz-abayafilmmaker-on-a-voyage/

112 Cruz, Marinel. Marilou Diaz-Abaya in Her Last Hours High on a “Starry, Starry Night…” (Philippine Daily Inquirer, 2012, Oct 10).

MARILOU DIAZ-ABAYA FILMOGRAPHY

(All theatrical feature films unless otherwise noted.)

Tanikala – Chains, 1980. Screenplay: Edgardo Reyes from Pablo S. Gomez story. Produced by: Cine Filipinas.

Brutal, 1980. S: Ricardo Lee. Bancom Audiovision.

Macho Gigolo, 1981. S: Oscar Miranda. Lotus Films.

Boystown, 1982. S: Jose Javier Reyes. Regal Films.

Moral, 1982. S: Ricardo Lee. Seven Stars Productions.

Minsan Pa Nating Hagkan ang Nakaraan – Yesterday’s Kiss… Tomorrow’s Love, 1983. S: Raquel Villavicencio from story by Carlos Caparas. Viva Films.

Karnal – Of the Flesh, aka Carnal Desires, 1983. S: Ricardo Lee based on article about a legal case by Teresita Añover Rodriguez. Cine Suerte.

Alyas Baby Tsina – Alias Baby China, 1984. S: Ricardo Lee based on real life case of Evelyn Duave Ortega. Viva Films.

Sensual – Of the Senses, 1984. S: Jose Javier Reyes. Regal Films.

Kung Ako’y Iiwan Mo – If You Leave Me, 1992. S: Amado Lacuesta. Regal Films.

Ang Ika-Labing Isang Utos: Mahalin Mo ang Iyong Asawa – The 11th Commandment: Love Thy Spouse, 1994. S: Jose Dalisay, Jr. Regal Films, Star Cinema.

Ipaglaban Mo – Redeem Her Honor, 1995. S: Ricardo Lee based on legal cases. Star Cinema.

May Nagmamahal sa Iyo – Madonna and Child, 1996. S: Ricardo Lee, Shaira Mella-Salvador. Star Cinema.

Milagros, 1997. S: Rolando Tinio. Merdeka Films.

Sa Pusod ng Dagat/In the Navel of the Sea, 1998. S: Jun Lana. GMA Films.

José Rizal, 1998. S: Ricardo Lee, Jun Lana, Peter Ong Lim. GMA Films.

Muro Ami – Reef Hunters, 1999. S: Ricardo Lee, Jun Lana. GMA Films.

Bagong Buwan – New Moon, 2001. S: Ricardo Lee. Star Cinema.

Noon at Ngayon – Then and Now, 2003. S: Ricardo Lee. Star Cinema.

Silsilah: Dialogue Movement for God’s Peace (video documentary), 2004. S: Marilou Diaz-Abaya. Silsilah Peace Institute.

Maging Akin Muli – Be Mine Again (TV movie), 2005. S: Marilou Diaz-Abaya. Jesuit Communications Foundation.

Ikaw ang Pag-Ibig – You Are Love, 2011. S: Marilou Diaz Abaya. Archdiocese of Nueva Caceres, Marilou Diaz-Abaya Film Institute.