Brutal (1980) premiered at the Metro Manila Film Festival, the annual year-end period when only Philippine films could be screened in Manila theaters, thus giving the industry (which at that time produced some 200 feature-length films a year) a respite from the year-long stranglehold on theatrical bookings by Hollywood imports. There had been naysayers during the shooting of Brutal, warning about the commercial perils of making a film that developed through flashbacks and flashbacks within flashbacks. 21 But Brutal became a surprise box office hit, coming out of nowhere and without a big studio machinery promoting it, handily beating even box office action king Fernando Poe Jr,’s Ang Panday/The Blacksmith, and garnering the most trophies at awards night. It went on to rack up a host of nominations and awards from industry and critics’ award-giving bodies. Abaya, just months earlier lost in limbo and feeling rejected with Tanikala’s failure, had suddenly arrived. One sure sign was when she got an envelope in her office one day that contained a memo pad with the letterhead of Ishmael Bernal, the brilliant director who, with Lino Brocka, was then leading the Second Golden Age of Philippine cinema that they started in the mid-70s. It said: “Congratulations for a brilliant movie, Ishmael Bernal. PS. I’ll see you one of these days at Jack’s.” 22

Soon, they met each other at that sleazy watering hole. Bernal sat himself in front of Abaya and gave her another card of congratulations. Their first chat went on from 10 PM to 7 AM. This flamboyant French-speaking man with an air of hauteur intrigued her. She wanted to enter his universe of Ermita artists, Malate intellectuals, and books forbidden by the nuns. The interest was more than reciprocated. From then on, Bernal became Abaya’s mentor, closest travel companion, harshest yet most supportive critic, and for all intents and purposes a member of her family. 23 24 Beyond introducing Abaya to the works of authors like Sartre, de Beauvoir, and Malraux, he also taught her focus. She recalled that Bernal was unafraid of scandal and uncertainty: “There’s also another thing that I learned from him… and also from Lino (Brocka)… and that was… to love art is to embrace poverty and uncertainty… and not to be afraid of the uncertainties of an artist’s lifestyle… to sacrifice security, material wealth, regular family… to become a dedicated filmmaker which is also to say, to become a public servant, at the beck and call of the artist as a public citizen.” 25

With the sudden rise of Abaya’s reputation, one might think that she could now look forward to more options in projects to take on. It is therefore curious that she chose to direct Macho Gigolo (1981) next. The film couldn’t be more different from Brutal, and perhaps this was what attracted her to the project. Written by Oscar Miranda, who had worked on the screenplays of two of Bernal’s less celebrated but nevertheless affable films, the film tells the story of Manny (Lito Lapid) who takes on one job after another – Ferris wheel operator, piggery worker, chauffeur, beerhouse waiter – but keeps losing them because he’s too good of a Samaritan, always getting into fistfights in order to defend some abused stranger. He makes his way to Manila from his native Olongapo and there becomes a kept lover for older woman Chaka (played with deadpan brio by veteran diva Celia Rodriguez). The film is a mostly mindless hybrid of choreographed fistfights and sex comedy. The comedy part revolves around older women (including Liza Lorena and Rosemarie Gil) lusting after younger men (including Orestes Ojeda and Mark Gil). But with almost metronomic regularity, it is the martial arts fights, unimaginatively choreographed, that dominate the film, as if Abaya wanted to show that she could outdo any other director in staging nonstop fight routines that appeal to the male action crowd.

Abaya then accepted an offer from Mother Lily Monteverde of Regal Films, the most powerful production company at that time, for another male-oriented project, to star two young actors, Gabby Concepcion and William Martinez. Boystown (1982), with a screenplay by a new young writer, Jose Javier Reyes, was promising enough, with the kind of social context that most serious projects of that time tried to integrate into their stories: Life among the wards of the Boystown orphanage and the economic difficulties and social prejudices that they had to cope with after leaving the institution. Martinez plays Arnel, the young man who leaves the institution, hoping to make his way in the outside world. Left behind is Bobet (Concepcion) whose friendship with Arnel had suddenly turned to hatred when Bobet’s brother died in an accident blamed on Arnel.

Prejudices and preconceptions in the bigger world about Boystown and their wards prove daunting for Arnel. They are deemed to be problem kids, unreliable, even thieves, and Arnel finds it difficult to find a job. He eventually gets one as a warehouse worker in a department store, but a supervisor, jealous of Arnel’s growing relationship with salesgirl Laida (Maricel Soriano) frames him for theft. Arnel goes back to Boystown and finds Bobet and the other boys confronting a gang of thugs who hang out in the periphery of the institution, terrorizing them.

The film was shot in the Boystown institution itself in Marikina and Abaya used its actual wards as extras. The contrast between the army of scrawny, dark-skinned boys and the Western-looking leads who are older and head-and shoulders taller, tends to be persistently distracting – the real Boystown wards often seem more like part of the props department than the cast. Instead of according authenticity, shooting on the actual location produced the opposite effect. Add to this the sudden appearance of thuggish brutes to drive the story to a climactic end, which comes across as overused plot device than organic development of the story’s premise or theme.

Years later, Abaya would be candid on Boystown and Macho Gigolo: “Probably, I would be embarrassed to watch them now. Even to show the films to my sons. But at that time I was having fun. Directing wasn’t a career then. It was an excuse for a party.” 26

Abaya’s next film Moral (1982) revealed a renewed commitment and rededication to her art and career. Indeed, it marked a quantum leap in Abaya’s filmography and has become one of the classics of Philippine cinema. Written by Lee, the film is almost four films in one, as it follows in almost novelistic plenitude the mostly separate and only occasionally intersecting lives of four college friends at the University of the Philippines during the height of student activism just before the declaration of Martial Law in 1976. It was a time of hope that youthful involvement would bring forth a more open and responsive political and moral direction for the country. It was also a time of moral flux and all four women find themselves in situations when old values and principles no longer apply.

Maritess (Anna Marin), an aspiring writer, marries Dodo (Ronald Bergendahl) whom she finds out to be a traditional Filipino male chauvinist with an extended family that expects her to settle down in the role of submissive wife and in-law.

Joey (Lorna Tolentino) is desperately in love with student activist Jerry (Michael Sandico) but he continually rebuffs her, however gently. She compensates by deeming herself liberated as she sleeps around in empty encounters with men. In the meantime, she blames her troubles on her mother Maggie (Laurice Guillen) who separated from Joey’s father and has found another man.

Kathy (Gina Alajar) will do anything even if it’s against her will and her morals, provide sexual favors to an old man and a lesbian talent agent she equally despises, in her obsession to succeed as a singer. The only thing she seems unable to stomach is recognize and accept that she just can’t sing to save her life.

Sylvia (Sandy Andolong) is a single mother who shares custody of a son with her gentle and responsible ex-husband Robert (Juan Rodrigo). An attractive woman, she has tried to meet other men but could find no one whom she could love in much the same way as she does Robert even though he is now co-habiting with another man Celso (Lito Pimentel). She precariously treads new territory as she continues to latch on to her love for Robert to the point of befriending Celso.

The film brims with unforgettable developments as it broadens into an epic mosaic of the early 70’s and its moral ferment. There’s the scene where Joey watches the object of her obsession, Jerry, tenderly making love with another woman Nita (Mia Gutierrez) who has not an inch of Joey’s looks or personality. Or the one where Joey learns from Nita that Jerry was killed by government agents, and Joey’s jealous hatred of Nita turns into shared pain and respect. There’s the scene where, after another failed date, Sylvia comes to Robert’s home and quietly dances with him and his lover. Or one where Maritess finally finds the courage to leave her husband, his family, and all the security that the marriage could bring.

The film amply displays Abaya’s command of actors and complex mise-en-scène, Fiel Zabat’s meticulous production design, and Manolo’s sensitive camera work. Hoping to surpass the success of Brutal, Abaya and Ejercito entered Moral at the 1982 Metro Manila International Film Festival. They were disappointed. It was mostly ignored by critics and the public who were not used to films roving across four lives without a concrete structure, let alone one with no big-name stars (Lorna Tolentino was just at the start of her ascent to superstardom then). 27

Abaya recalled: “Generally, the audience did not connect. But this was something I was not surprised at at all. While making it, I was already feeling very anxious and uncomfortable about the fact that I thought this is too personal. Baka ako lang ang makakaintindi nito. (I might be the only one to understand it.) I was really hurt when I felt it was rejected. Even if you anticipated that rejection.” 28

But the stock of Moral has only risen since, far overshadowing Brutal in esteem (and aptly so) and now regarded as one of the great works of Philippine cinema. The Philippine’s most prestigious critics group, the Manunuri, named it one of the ten best films of the 1980s, a distinction for one made when the Second Golden Age of Philippine cinema (from the mid-70s to the mid-80s) was still in full swing and an unusual number of masterworks were being produced by directors like Bernal, Brocka, Mario O’Hara, Mike de Leon, Laurice Guillen, and Celso Ad Castillo. The film became the first of Abaya’s works to attract foreign attention when it received the 1984 British Film Institute’s Outstanding Film of the Year award, from the very city where Marilou, Manolo, and their soundman Amang Sanchez, all once trained while dreaming of becoming known filmmakers.

Two of Bernal’s successful domestic dramas, Relasyon/Relationship (1982) and Broken Marriage (1983), would have been in Abaya’s mind when she signed on with major production company Viva for her next project, also a domestic drama, Minsan Pa Nating Hagkan ang Nakaraan/Yesterday’s Kiss… Tomorrow’s Love (1983). Both of Bernal’s films had top-billed two of the country’s most enduring superstars, Vilma Santos and Christopher de Leon, and Abaya’s own project would feature the same actors. That it shared so many common elements as the great master’s works would have been both cause for excitement and trepidation for Abaya. For the script, she hired a young writer, Raquel Villavicencio, who had co-written Relasyon with Bernal and Lee. Based on a story by popular komiks writer Carlo Caparas, the film follows the obsessive relationship between Rod (de Leon) and Helen (Santos) that broke up when Rod left to study in the United States and that reignited as soon as he came back. The only problem is that Helen is now happily married to a much older man, Cenon (Eddie Garcia). At first, Helen resists Rod’s renewed pursuit but her barriers eventually break down and she starts to meet him in guilty trysts. As Helen refuses to leave her husband, Rod insinuates himself into Cenon’s good graces and gets himself hired as architect for a house that Cenon is building for Helen. She tries to break their affair once and for all, but Rod can’t be easily shaken off, especially after Helen gets pregnant and Rod is convinced that the baby is his. This dance of obsession, temptation, and guilt leads the lovers to tragedy.

Abaya displayed style and maturity in her handling of a story which in most hands would be an occasion for melodramatic excess. As with the majority of Abaya’s works, the attention to production design, cinematography (by Manolo) and pacing is evident. The film did not reach the sublime elegance and wit of Bernal’s best domestic dramas like Relasyon. But it was a cut above the majority of domestic dramas of the day and need not find an excuse for its unpretentious, modest study of romantic obsession.

It’s worthy of note that Abaya’s great masterworks of this period were produced not by the major commercial studios like Viva or Regal, but by smaller producers who had more, or everything, to lose in taking on ambitious, risky projects. Abaya’s next film began with a mysterious phone call. It was from someone who called himself M7, asking if they could meet for a possible project. She soon learned from a publicist that M7 was the alias of an independent producer named Ben Yalung. The Abayas and Yalung met at a dinner where Yalung’s friend, a relatively unknown actress, Cecile Castillo, was also invited. Yalung, who had produced only one film under his company, Cine Suerte, said that Abaya could make any film she wanted with the one condition that it feature Castillo in a starring role. It struck Abaya that Castillo’s face had an intriguing “period” look. 29 During the course of the dinner, Yalung handed Abaya a magazine clipping from Mr. and Ms. magazine of a legal story called “To Take a Life” reported by Teresita Añover-Rodriguez about a woman who killed a father-in-law who had sexually abused her. 30 31

Lee came on board as scriptwriter and Abaya told him about Castillo’s period look. She conjectured that the story could gain an extra dimension if they set it in an earlier period like the 1930s, a time when attitudes and morals were transitioning towards a greater liberalism from the old conservatism of Spanish colonial times. 32

To get the period look and feel, the Abayas and production designer Fiel Zabat studied all the paintings by Fernando Amorsolo and books that they could find on him. They started with the paintings that Abaya grew up with and that were still hanging on the walls of her parents’ house. For the film’s location shooting, Abaya and Zabat searched among the old towns in Central Luzon and settled on Gapan, Nueva Ecija and its surrounding towns. It was a boon when the great old stone house that Abaya fell in love with happened to be owned by Zabat’s distant aunt who welcomed Abaya and her crew as family. Residing nearby where other relatives of Zabat’s and several of the authentic period costumes for the film were lent by her grandmothers. 33

Zabat, whose production design eventually won both industry and critics group awards, gives us a picture of Abaya’s directing style, comparing it with other famed directors that Zabat had worked with. If Lino Brocka was more like a captain leading his troops and Bernal an autocratic professor, Abaya was more like a sister or best friend sharing an adventure. Zabat recalls never seeing Abaya berate an actor in front of others, no matter how frustrating the actor’s faults; she would instead signal the actor to the side and talk matters over quietly. She would continually encourage everyone, including the makeup artist and production assistants, to find holes in story and staging, and to freely express creative ideas that might add another bit of texture or authencity to a scene. 34

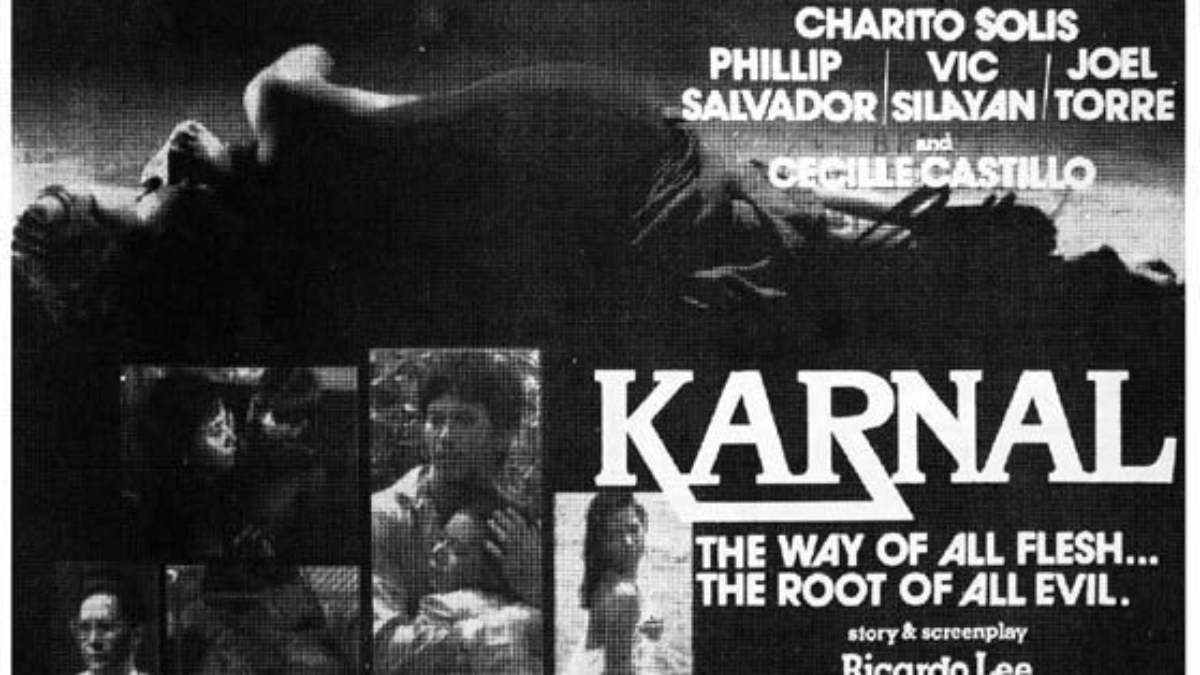

Karnal/Of the Flesh (1983) has such a classic plot, simple and complex all at once, it would be instructive to inspect a more detailed outline. (And this being a critical survey, “spoilers” are not inappropriate.)

The film opens with a steely-looking woman (Charito Solis) in present-day metropolitan San Juan, addressing us, with a lurking tone of disquiet, about the story of her ancestors in a faraway village called Mulawin. The film soon takes us to a glowing day in the past when Narcing (Philip Salvador) arrives back at the family’s old ancestral mansion with his new wife Puring (Cecille Castillo) whom he met in Manila. He introduces Puring to his father Gusting (Vic Silayan), landlord of a big hacienda; his sister, the diffident Doray (Grace Amilbangsa); and Doray’s husband Menardo (Pen Medina), so submissive to Gusting that he has become a cipher of a man.

Father and son’s reunion is tense. Gusting has not lost his resentment at Narcing’s decision to disobey him by leaving his place as the landlord’s son and trying his luck in Manila. He shows no sympathy now that his son has come back, a failure in the city. Adding to the tension, Gusting is struck by Puring’s resemblance to his dead wife. Moreover, Puring shows a frankness and directness that would have been natural in Manila where she was orphaned early and learned to work and support herself, but her manner strikes the traditional, feudalistic Gusting as insolent.

Narcing, who would rather have a town job than work in the hacienda, finds a spot at the provincial capitol and is away most of the day. He reminds Puring that she should not leave the house and go about the village on her own, as only loose women do this. Puring soon tires of being confined to the house and domestic housework and she tries to persuade Narcing about going back to Manila but he angrily rebuffs her.

She soon learns from Doray that Gusting’s wife hanged herself a few years back after Gusting accused her of infidelity and dragged her naked in front of the villagers. Gusting, for his part, is obsessed with his daughter-in-law’s resemblance to his wife. He initially represses these impulses, finding release in wielding an oppressive hand over the family members and his farmers. One day, while Narcing is away, Gusting prevails on Puring to wear his wife’s old clothes and jewelry. The sight overwhelms Gusting and he forces himself on Puring but is interrupted when his daugher comes into the room.

Puring tries to find some respite from the house’s oppressive grip by talking to the townspeople who look with suspicion at a woman going around by herself. She finds solace in a friendship with the town outcast, the mute coal-peddler Goryo (Joel Torre). Word goes around about her activities and Narcing beats his wife with rage before asking forgiveness in a pattern that would only become too familiar.

One day, Puring loses track of time and overstays in Goryo’s hut. Gusting finds her and after dragging her back to the house, accuses her of adultery in front of Narcing. This leads to a fight between father and son where the father wrestles his son to defeat. When Narcing learns that his father had tried to ravish his wife, he picks up a bolo knife and decapitates his father. Puring soon gives birth to a malformed infant with horns and, wishing to end its suffering, buries it alive. The timid Doray flees the house and her passionless marriage and tries to find her real love Jose. The repressed spinster who is narrating the story is their daughter, and though the past is long gone, its actors long buried, it still manages to exert its destructive influence on her life.

Under Abaya’s inspired direction, Karnal brings together a number of major artists of Philippine cinema at the height of their powers: Lee, with a poetic screenplay and a flair for dialogue that come across as both lyrical and almost insolently direct at the same time; Manolo, whose cinematography and lighting evoke a haunted world; Zabat, whose production design has a diaphanous quality that suggests the permeability of past and present; and Ryan Cayabyab, who wrote and orchestrated a musical score that heightens and sustains the film’s balance of menace and rhapsody.

Indeed, with an irony that attests to the transformative power of art, Karnal comes across as exquisite and delicate, despite the rape, patricide, suicide, beheading and infanticide that drive its story. Well, almost all of the film. Marring the film’s elegance, an extended passage after the infant burial on through Narcing’s bloody suicide in a Manila jail is so unremittingly punctuated by wailing that it pushes the film over to melodrama. Such strident miscalculation could have sunk many another film, but with Karnal, it only attests to the underlying beauty and power of the work. The film regains grace and balance after the suicide, which is sustained to its haunting end. And indeed, despite its evident flaw, Karnal remains a great masterwork with the hindsight of 30 years.

Karnal can be viewed validly from a number of angles: As a metaphor of the iron-fisted Marcos dictatorship then holding the Philippines in its grip; an indictment of a patriarchal, feudalistic system that even now continues to suppress women and the weak in the Philippines and other countries; a psychological study on the porousness of past and present; and a Greek tragedy, with its sense of inevitability and stark depiction of man’s eternal passions.

Karnal premiered at the 1984 Metro Manila Film Festival and though it won the best picture trophy and others for cinematography and sound design, it was initially ignored by the public who were used to more overwrought handling of their dramas. 35 In any case, the film’s reputation continued to rise and by decade’s end, it was hailed by the Manunuri critics group as one of the ten best films of the decade along with Moral. It also became the second of Abaya’s films to gain international attention at film festivals including Sceaux and Paris and eventually, at retrospectives in Munich and Düsseldorf.

Karnal became known as the third in Abaya’s groundbreaking trilogy of feminist films. It’s often said, with good reason, that to refer to a director as a woman director is a gross form of male chauvinism. But it’s appropriate to touch on the subject of women directors here. Abaya herself did not shrink from referring to some of her films as a “feminist film by a woman” yet she never saw herself as any less than equal to her male counterparts. While Philippine women directors, particularly the prolific Susanna C. de Guzman and Fely Crisostomo, were not unknown in the industry’s history, one could count their numbers with the fingers of one hand at any given time and the studios generally confined them to working on romantic melodramas. The only other female directors active when Abaya started working were Laurice Guillen and Lupita Aquino-Concio, both of whom directed some great classics of their own, among them Salome and Tayong Dalawa/The Two of Us by Guillen, and Minsan Isang Gamu-Gamo/Once a Moth by Aquino-Concio. In ambitiousness of projects and budget, box office records set, variety of themes and genres, and international recognition, Abaya would eventually surpass them all, and indeed most other directors of whatever gender or sexual orientation; and in this way, the new paths she opened and rights she procured have accrued to all filmmakers irrespective of gender.

References

21 Ibid. 1, p. 51.

22 Ibid. 7, p. 256

23 Ibid. 1, p. 46.

24 Yuchengco, Mona Lisa. Marilou Diaz-Abaya: Filmmaker on a Voyage, (documentary film, 2013), time code: 6 min. in.

25 Ibid. 14 min. in.

26 Ibid. 7, p. 259.

27 Ibid. p. 257.

28 Ibid. p. 258.

29 Ibid. p. 259.

30 Ibid., p. 259.

31 Noted in Karnal’s closing credits.

32 Ibid. 7, p. 259.

33 Ibid. 4.

34 Ibid.

35 Ibid. 7, p. 259