Written By: Nathan Liu

This article contains spoilers.

As the credits rolled on the final episode of “Kim’s Convenience,” the Canadian sitcom about a Korean family running a store in Toronto, I had one thought in my mind, “what a waste.” Between the inconclusive ending, inconsistent characterization, and constant continuity breaks, the show left a LOT to be desired. And that’s without factoring in the behind-the-scenes drama and intense public pressure that the series, as the first Canadian show with a majority Asian cast, had placed on it.

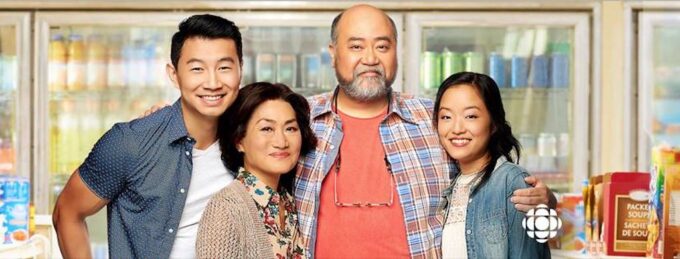

“Kim’s Convenience” began its life back in 2011 as a play. Written by Ins Choi, and based on his own experiences working in a convenience store with his parents, the show was popular when it first premiered. In March 2015, CBC Television announced that it was developing a series based on it, which premiered in 2016, and ran until 2021. Both the play and the TV series focus on Mr. and Mrs. Kim — played by Paul Sun-Hyung Lee and Jean Yoon, respectively — Korean immigrants who run a small convenience store in Toronto. They have a daughter, Janet — played by Andrea Bang — who dreams of becoming a professional photographer, and a son, Jung — played by Simu Liu — who has a strained relationship with his father due to his criminal past. Though by the time the series begins, Jung has gotten his life together. He’s even found a job at a car rental business, run by Nicole Power’s Shannon, who later becomes his girlfriend.

The show was popular when it first premiered, earning praise for its acting, light humor and representation, particularly how it introduced Korean culture to an audience that would otherwise not know about it. And it helped boost Simu Liu’s profile for him to get cast as Shang-Chi in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Though it wasn’t without controversy. Right out the gate, the show attracted criticism regarding Mr. and Mrs. Kim’s accents, which some felt were over-the-top and used as punchlines. And several people online pointed out that the character Nayoung, Janet’s cousin, dressed and spoke more like a Japanese Otaku than a girl from South Korea.

The cast defended these creative decisions, particularly the accents. In a 2016 interview with Maclean’s, Paul Sun-Hyung Lee pointed out that Asian immigrants oftentimes do speak like Mr. Kim, and that the characters had depth and humanity beyond how they talked. Which is true. The accents certainly are broad, and a lot of the humor does boil down to “ha ha, these immigrants talk funny,” but that doesn’t change the fact that people who speak English as a second language, like Mr. and Mrs. Kim, usually have accents. And the show does give the characters nuance beyond the way they speak.

Both Mr. and Mrs. Kim are given back-stories, and there are several moments, especially when the two are alone together, that they get to be vulnerable and show real humanity. My favorite is in the second to last episode where Mrs. Kim, who’s stopped praying after getting diagnosed with MS, breaks down in front of her husband, saying she fears God has abandoned her. It’s a great scene, and there are several moments like that scattered throughout the series, which help to elevate Mr. and Mrs. Kim beyond stereotypes.

That said, it does feel like the showrunners and writers went out of their way to make “Asians can’t speak English” jokes, especially when you realize how weird it is that two Korean immigrants are conversing with each other, not in their native Korean, but in heavily accented English. Yes, neither Jean Yoon nor Paul Sun-Hyung Lee can speak Korean well, and some jokes only make sense in English, but still. It strains credibility.

What’s most irritating when you binge the series is how little consistency and continuity there is. Not just between seasons, but even between episodes. Case in point; Janet’s love-life. Across the show’s five seasons, the writers never seem to be able to agree on who, or even what, she’s into. As a result, love interests are introduced and then dumped without any explanation as to who they are or why Janet stops going out with them. In the first season, she’s dating a cop named Alex, who happens to be Jung’s childhood friend. By season two, however, Alex has disappeared, with no explanation as to where he went or why. Instead, Janet is now dating a guy named Raj, whom they don’t bother to explain how she met, or how long they’ve been together. And in the final season, without any buildup or preamble, she likes girls, actually kissing one in front of her dad. It’s completely dropped by the next episode.

There are other continuity hiccups — Shannon’s roommate turns into a completely different person between episodes, and she herself shifts from a tone-deaf, far-too-handsy boss in the first season to a harmless sweetheart who’s perfect for Jung in the second.

Yes, sitcoms, by virtue of being sitcoms, are less serialized than dramas. The whole idea is that you’re supposed to be able to pick up at any point and enjoy a self-contained story. And it’s worth remembering that episodes of “Kim’s Convenience” were meant to be seen once a week, and not consumed in a single sitting, thus allowing space for audiences to forget about what they saw last time. But even acknowledging all of that, there are tons of other sitcoms — “Friends,” “Seinfeld,” “30 Rock,” “The Good Place” — that both acknowledge their continuity, and provide in-story reasons for why certain characters leave. And that’s to say nothing of the ending, which is incredibly abrupt and doesn’t wrap up any of the major plot threads, likely due to all the behind-the-scenes drama.

As soon as the final season aired, cast members, such as Simu Liu and Jean Yoon, began publicly airing their grievances regarding the show’s direction, and subsequent cancellation. In a lengthy Facebook post, Liu claimed that the overwhelmingly-white writers room and producers oftentimes ignored suggestions that the Asian cast members made, and frequently pushed racist storylines and jokes. And when people criticized him, and suggested he might have been lying, Jean Yoon came to his defense. In a Twitter post, she confirmed that Ins Choi, the original playwright, didn’t actually have much say in the direction of the show or the scripts; that the non-Asian showrunner, Kevin White, was the one dictating everything. Which would have been bad enough, without considering the fact that the show was supposed to have a sixth season, but was suddenly and abruptly cancelled, much to the dismay of the cast.

In an interview with CBC back in April, Paul Sun-Hyung Lee expressed his deep sadness at not being able to wrap the show up properly, to “do our victory lap,” as he put it. I haven’t been able to find a concrete reason for why the show was cut short. And, apparently, neither has the cast. In the same CBC interview, Lee explained that he didn’t really know why the show ended, that it was just a thing that occurred. A few theories have been floated, such as the idea that the network didn’t want to continue the series after the co-creators left. But that explanation falls apart when you remember that Ins Choi didn’t have much control to begin with, and that many shows continue without their initial creators. Aaron Sorkin famously left “The West Wing” after season 4, and it ran for another 3 seasons. All of which makes the “Kim’s Convenience” cancellation even more infuriating.

Taking all this into account — the inconsistent writing, the stereotypical jokes pushed by white producers and writers, the abrupt, unsatisfying ending — it’s hard not to view “Kim’s Convenience” as something of a failed experiment. Its importance as the first Canadian sitcom with a majority Asian cast cannot, and should not, be downplayed. And its popularity will hopefully lead to more TV and film projects created by, and starring, Asian Canadian artists. But on its own, “Kim’s Convenience” is a flawed work whose legacy may simply be that of a stepping stone towards greater representation.

All five seasons of “Kim’s Convenience” are available to stream on Netflix.