Written By: Nathan Liu

“Between 1907 and 1924, more than 20,000 young Japanese, Okinawan and Korean women journeyed to Hawaii to become the wives of men they knew only through photographs and letters. They were called ‘picture brides.’ This film is based on their stories.”

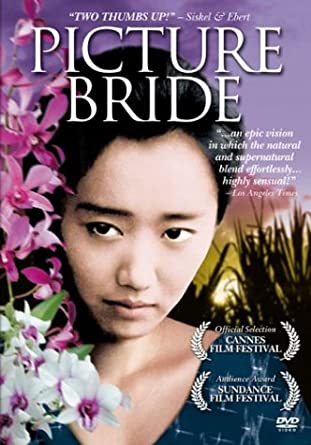

So begins Kayo Hatta’s “Picture Bride,” a beautiful, touching, yet sadly overlooked piece of Asian American cinema from 1995. The film tells the story of a Japanese girl (played by Youki Kudoh) moving to Hawaii in 1918, only to discover that her husband is much older than his photo, and that the conditions on the island are harsh. The movie was showered with praise upon its release, winning the Audience Award for “Best Dramatic Feature” at the Sundance Film Festival. And writer-director Kayo Hatta received a “Best First Feature” nomination at the Independent Spirit Awards.

Tragically, all the good reviews and accolades did nothing to help Hatta’s film career, and she never made another feature before her unfortunate death from drowning in 2005. She was only 47. And in the years since, “Picture Bride” largely fell into unfair obscurity.

This is an important film that should be watched. Not just because of its subject matter, but also because of who worked on it, and how the filmmaker was treated after the initial release. It’s a story that needs to be told, and it begins with the writer-director, Kayo Hatta.

Born in Hawaii and raised in New York, Hatta started making films while earning her masters at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). One of these was the original “Picture Bride.” Though conceived as a short about labor rights, the story had the potential to be extended into a feature. So she applied for a grant from the American Film Institute and went to Hawaii to research the subject further. After interviewing several surviving picture brides, she and her sister, Mari, turned the concept into a feature screenplay and began looking for financing. This was no easy feat.

As Hatta explained in the “making of” documentary, “… the only way I could raise that money was through grants and grassroots.” Lucky for her, there were lots of people in Hawaii willing to lend a hand. As she elaborated in the same doc, “This is only the second independent film that’s come out of Hawaii. So there was a huge community outpouring of support. Businesses donated food, porta potties and water. Women’s church groups offered their services to sew the costumes.” But even with all this community support, there were still problems.

The location they were shooting at was right by a military base, so they often had to stop and let helicopters fly through. It was also hot and muddy, and there were mosquitos everywhere. Because the film had such a low budget, certain members of the crew had to work for free, and even this wasn’t enough to keep them solvent.

At one point, they actually ran out of money, and Kudoh had to ask a Japanese lingerie company she’d previously modeled for to give them the rest of the budget. And while all of this was happening, Hatta was in a near constant struggle to maintain her creative vision. As she admitted in the “making of” doc, “There was a lot of convincing people that this was our vision. There were different parties that tried to turn it into something else. Something that they thought would be more marketable, more entertaining.”

Nevertheless, the film was completed, and screened at several film festivals, where it earned glowing reviews. Lisa Schwarzbaum of Entertainment Weekly said the film was “… a lyrical, elegantly composed drama.” While Peter Stack from the San Francisco Chronicle described it as an “”… exceptionally lovely first feature film by Kayo Hatta.” Here were the biggest critics in the world, heaping praise on their movie. Their small, independently-financed movie, starring, written, directed and produced by Asian American women. It must have felt like victory, like they’d reached the top of the mountain and had a chance to drink from the fountain there.

But that sweet taste of victory was quickly washed away by the bitter pill of disappointment. Hatta never got the chance to direct a feature again, and it wasn’t for lack of trying. In 1999, she narrowly lost out on the chance to direct “Snow Falling On Cedars,” a big-budget drama about Japanese American internment, which also starred Youki Kudoh. She tried, and failed, to get funding for an adaptation of Cynthia Kadohata’s acclaimed novel “The Floating World.” She continued to make shorts, one of which, “Fishbowl,” aired on PBS in 2007. And she acted as a mentor to other emerging filmmakers, teaching courses at UCLA and the Art Institute of Los Angeles. Nevertheless, after her death in 2005, both she and “Picture Bride” faded from public memory. Something that, in a completely fair world, would not have happened, given the movie’s level of prestige.

“Picture Bride” was a film that screened at major festivals like Sundance and Cannes, got glowing reviews, and was even picked up by an established distributor, Miramax, who released the film on DVD in 2004. If a movie like that was made now, then Hollywood would likely snatch up its director for some tentpole project. That is, after all, precisely what happened to Chloe Zhao.

Like Kayo Hatta, Zhao premiered her first feature, “Songs My Brothers Taught Me,” at the 2015 Sundance Film Festival, and was nominated for “Best First Feature” at the Independent Spirit Awards. Unlike Hatta, however, Zhao was able to procure funding for her subsequent films, and was eventually hired to direct a major blockbuster, Marvel Studios’ “Eternals.”

Hatta never got the chance to do anything like that, and I can’t help but wonder if the key difference between her and Zhao was not talent, but simply when each of them was alive.

Hatta was born in 1958, and when she started making movies in the 1990s, there just wasn’t a demand in mainstream Hollywood for women directors, directors of color, or Asian American stories. Now, thanks to the success of films like “Crazy Rich Asians,” “Searching” and “Minari,” studios have finally woken up to the fact that there’s a large, untapped market of Asian American viewers eager to see films made by and about themselves. So it seems like Zhao was just lucky to come of age in a more enlightened time than Hatta.

It’s also worth noting that Zhao’s films aren’t about Asian or Asian American identity at all, so perhaps they’re more palatable to white studio heads. And she is the daughter of a wealthy Chinese steel magnate. So it’s possible that, unlike Hatta, who had to piece-meal her budgets and rely on the kindness of strangers, Zhao was just able to pay for her films by herself.

Regardless of why it fell into obscurity, “Picture Bride” is a movie that should be rediscovered and celebrated as a landmark achievement, not just in Asian American cinema, but also independent filmmaking in general. Its cinematography is gorgeous. The production design and scale of the film, which includes a massive cane field fire, is impressive, especially considering the low budget. Youki Kudoh and Tamlyn Tomita — whom you might recognize from “The Karate Kid Part 2” and “The Joy Luck Club” — play well off of one another. The love story between Kudoh and her new husband, played by Akira Takayama, is actually quite sweet. And the film is surprisingly intersectional. We see Japanese and Filipino laborers working in the fields, with the two groups even getting into a fight over pay disputes, but eventually going on strike and forming a union.

This is a movie that truly was ahead of its time, and should be studied and preserved. Not just because of its subject matter, but also because of the extraordinary efforts of Kayo Hatta and her team of remarkable Asian American women. They deserve to be remembered, and by watching and sharing “Picture Bride,” the fruits of their labor, we can give them something that we all strive for; immortality.

“Picture Bride” is available to rent and purchase on Amazon.