Written By: Nathan Liu

Producers. They’re crucial to filmmaking, yet few people seem to know what they actually do. I certainly didn’t. For years, if you’d asked me what I thought a producer was, I’d probably have said, “A fat, cigar-chomping man, who only cares about the money, who’s constantly harassing the actors, and who’s always interfering with the director’s vision.” A reductive answer, shaped by the likes of Harvey Weinstein. But as I soon found out, producers are more than mere bean counters.

They’re the showrunners on film shoots. Not only do they hire everyone — from the writer, to the director, to the cast and crew — but they’re also the ones who find locations, provide food and housing, and are often on-set for the entire production, helping to shape the look and tone of a movie. It’s why they, and not the directors, win Best Picture at the Oscars. Because in terms of creating the whole movie, seeing the “big picture,” they really are the ones who make it happen. And perhaps no one exemplified that better than Ismail Merchant, the first Indian producer to be nominated for Best Picture, and whose fastidious attention to detail created a brand name that’s still recognizable decades after his death.

Born Ismail Noor Muhammad Abdul Rahman in present-day Mumbai in 1936, Ismail Merchant grew up in a wealthy, well-connected Muslim family. These connections are what allowed him to develop a personal relationship with the actress Nimmi by the age of 13. And it was this relationship that spurred his love for film, since it was she who introduced him to the various studios in Mumbai, then the heart of India’s film industry.

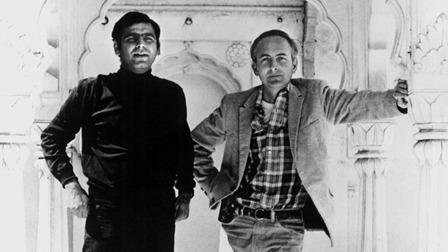

Deciding that cinema was what he wanted to spend his life creating, Merchant moved to New York at the age of 22, changed his name and pursued various film projects while working odd jobs. One of these was acting as a messenger for the United Nations, where he was able to persuade various Indian delegates to fund his films. One of these projects, a short dance film entitled “The Creation of Woman,” was screened at the 1961 Cannes Film Festival, and later received an Academy Award nomination for Best Live Action Short. That same year, Merchant formed a film company, Merchant Ivory Productions, with the man who would be his romantic and creative partner for the rest of his life, director James Ivory.

The two met in 1959 at the Indian Consulate in New York, where Ivory’s documentary, “The Sword and The Flute” screened. They quickly bonded, particularly over their shared desire to create English films in India, aimed at the international market. And that’s precisely what they did.

In 1963, the pair premiered their first feature, “The Householder,” based on a book by German-born novelist Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, who would go on to write many of Merchant Ivory’s best-known movies. The film was a critical success, and the first Indian-produced picture to be distributed by a major American studio, Columbia Pictures. However, it wasn’t until the 1970s that their partnership “… hit on a successful formula for studied, slow-moving pieces … known for their attention to tiny period detail.” Their first success in this style was Jhabvala’s adaptation of Henry James‘s “The Europeans,” and would be expanded upon in the 1980s and ‘90s, when the company started making movies in the UK.

Perhaps their best-known works — 1986’s “A Room With A View,” 1992’s “Howard’s End” and 1993’s “The Remains of the Day” — come from this period, and really helped solidify Merchant Ivory as a brand. Not only were all three films critical successes, with Merchant earning Best Picture nominations for each, but they also helped create an image in the minds of general audiences as to what a Merchant Ivory production involved: A 20th-century period piece, starring pedigreed British actors like Anthony Hopkins, Helena Bonham Carter or Emma Thompson, set in a big house and featuring gentile characters experiencing disillusionment and tragic entanglements.

This image became so well-known that the term “Merchant Ivory” has since made its way into common parlance as a description of a genre, rather than a studio. When I interviewed Jonathan Tropper, the creator of “Warrior,” back in 2019, he stressed that they wouldn’t be taking the “Merchant Ivory approach,” which shows how big an influence the company, and Merchant in particular, had.

Merchant wasn’t just the money behind the movies. As Ivory explained in an interview after his partner’s death, Merchant was very heavily-involved in shaping the pictures. In many cases, as with “The Householder,” he would choose the books they’d adapt, and would even make decisions regarding casting. But to his credit, he was never overbearing.

He, Ivory and Prawer Jhabvala made over 20 films together because they respected and brought out the best in one another. And it’s worth noting how unusually diverse their trio was, especially for the time. In fact, Merchant even joked about it in an interview, wherein he said, “It is a strange marriage we have at Merchant Ivory … I am an Indian Muslim, Ruth is a German Jew, and Jim is a Protestant American. Someone once described us as a three-headed god. Maybe they should have called us a three-headed monster!”

God or monster, there’s no denying the impact that Merchant left behind when, on May 25, 2005, he passed away at the age of 68. With films like “The Householder” and “Shakespeare Wallah,” he helped bring Indian cinema to the West. With pictures like “A Room With A View” and “Howard’s End,” he created a brand name that is instantly recognizable. And while modern audiences may find his films a bit slow and stuffy, and take issue with how rich and white their subjects usually are, there’s no denying his significance in the cultural landscape.

He was the first Indian producer to be nominated for Best Picture. His partnership with James Ivory, both professional and personal, lasted four decades and resulted in 44 motion pictures. He helped make international stars out of Hugh Grant, Daniel Day Lewis, Emma Thompson and Helena Bonham Carter. And he did all of this as a gay, Muslim, Desi man at a time when Western society was much less accepting of such things. All of this speaks to his talent and steadfast determination, and in my opinion, makes him the film producer poster child.