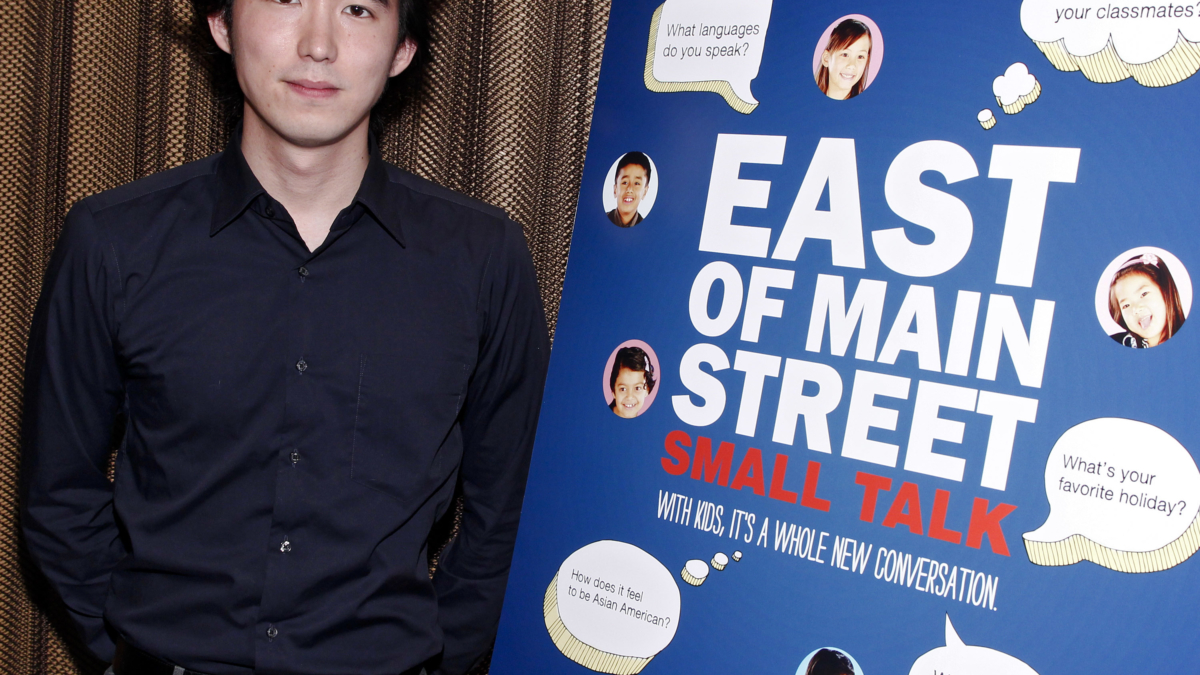

Photo by Brian Ach/Getty Images for HBO) 2012 Getty Images

CineVue had the pleasure to speak with Jonathan Yi, the Director of the HBO Series: EAST OF MAIN STREET. In this interview, he shares the process of gathering his cast and crew, and the heart, blood, sweat, and tears it took to make it happen.

CINEVUE: What was your inspiration for EAST OF MAIN STREET?

Jonathan Yi: In 2010, I got a phone call from Louis Tancredi, Executive Producer, of “East of Main Street.” He told me that HBO wants to create a program for Asian Heritage Month and asked if I’d like to pitch for the project, since they had done similar programming in the past, such as “The Blacklist” and “Habla.” The hope was to create a single program for the broad range of Asian Americans who would eventually watch the show.

I was honored to pitch for the project, but it was a daunting task to wrap my head around. Finding common ground between all of these cultures was difficult. The cultural differences within the East Asian community are vast, and South Asia is incredibly diverse on its own. To represent a common thread between all of Asia initially seemed nearly impossible, and I was worried about how many cultures would be unrepresented in a half hour show. I couldn’t rely on a unifying theme of a common language or culture. But after thinking about it, I realized that as Asian Americans, we have a lot more in common than we think–at the very least, we share a common experience as minorities of Asian descent. This is why I wanted to focus on the Asian American experience because it is an experience that unifies us. It’s a minority experience that transcends a lot of cultural barriers that viewers outside of our community can understand and relate to.

I wanted this show to be viewable and enjoyable for both Asians and non-Asians. I feel that in order to see more Asian Americans in regular programming, we need to reach a large audience; so that eventually, it won’t be strange to see more Asians represented in American media.

CV: Can you describe the casting process? How did you guys make your choice for artists/children?

JY: We’ve done this show for three years now and each year had its own casting challenges. For the first year, we were limited to shooting locally in New York City due to logistics and budget. I knew that a New York City based Asian American has a vastly different experience than someone who grew up Asian American in the midwest, so we did our best to find NYC transplants (such as Aman Ali from Ohio) to represent these various life experiences. During casting, we even spoke to Jeremy Lin’s coach at Harvard to get him into the show, but we couldn’t find the best time to make it work. This was obviously pre-Linsanity, so it’s funny to think that he could have been part of this show from year one. Our core team handled all of the casting ourselves through grassroots effort to get the word out around town. It was pretty grueling, meeting with so many people in a short period of time and also going to several places in NYC to recruit people, but I’m proud of the group we were able to assemble.

For the second year, we wanted to focus on food and family. Casting families on such short notice was a very tough challenge in the time frame we were given to work, so I suggested that we explore food and culture through Asian American celebrities who took non-traditional career paths. We did it because celebrities allowed us to quickly research about their family and history through preliminary web searches. Also, it gave us security in that they would be engaging, camera friendly and would have a built-in audience. We didn’t have the budget to reshoot if one of the chosen families was a bust, so this route allowed us to have a safety net that we’d come away with inherently interesting footage. In the end, the stories focused more on their careers and families more than food, but there is still an element of food in every segment.

This year we wanted to explore race through the eyes of children. Initially, we wanted to shoot in three American cities (New York, Los Angeles and somewhere in the South). We eventually could only afford two cities, so we decided to have our set in New York City and Irvine, California. New York was chosen because we live here, and Irvine was chosen because my sister pointed out how Asians in Irvine have a vastly different experience, since they are, in fact, the majority. I brought in my friend, David Stekert, who is a producer with experience casting non-actors. We used online media, such as Angry Asian Man, to get the word out, and sorted through tons of video submissions to decide who we would cast and shoot for the show. We also partnered up with a New York City school in Chinatown to recruit more kids and meet them in person.

Since we were walking into the shoot days without meeting most of the kids in advance, we made sure to schedule a LOT of kids in case some didn’t work out, so shoot days were pretty relentless, where we interviewed a revolving door of kids, each for 20 minutes back to back. Also, I wanted to highlight the differences in opinion between younger and older kids by making sure Irvine skewed younger, while New York skewed older. In Irvine, if Asian American children are truly the majority, they would most likely be unaware of racial tension at that young of an age. I wanted to be sure to get that point of view represented first. In New York, we had older kids carrying themselves slightly more seriously, and I knew that New York City is a place that is very much aware of race in general.

CV: During the Q&A, EAST OF MAIN STREET was described as a passion project for a lot of the cast and crew, can you elaborate on that?

JY: “East of Main Street” is an Asian Heritage program, and as such, doesn’t necessarily have a built-in venue to be seen. There isn’t a place designated for Asian programming, compared to similar programs like “Habla,” for example, where it has a place on HBO Latino. It is awesome that HBO decided to create a show like “East of Main Street” for the Asian American community, even when there isn’t a guaranteed return on investment. But, of course, our budgets have to be reasonable as a result. They fight for that little money we get and we’re glad that we have the opportunity to make this show.

As a result, everyone involved with this project takes a pay cut, and it takes a lot more time and dedication than other jobs because many of us are handling multiple tasks. But I think everyone involved really believes in the project and wants to make it the best thing we possibly can. I am always impressed by the quality of work that everyone from the top down does to help make this show as good as it is with limited resources available. It’s become something that our core group, Chrissie Hines (Creative Director) and Louis Tancredi (Executive Producer), really thinks about each year to make it as good as it can be.

What’s exciting now is that our show has always lived through HBO On Demand, and more recently on HBO GO as of season 2, but this year, HBO Family picked up “Small Talk” and has allowed us to reach a bigger audience.

CV: For SMALL TALK, a lot of the questions were open-ended–why? Were there any specific questions asked, but edited out of the final product? And did different ethnic groups react differently to different questions?

JY: Children tend to answer with yes or no responses and it wasn’t my initial intention to be heard as the interviewer, so we needed to ask open ended questions to elicit responses. I think our editor, Emily Sheskin, found a way to include most all of the topics and I’m thankful that she found a way to move seamlessly from topic to topic without the use of title cards.

Different ethnic groups didn’t necessarily react differently to different questions, but age differences and location (Irvine versus NYC) grouped the most common responses for the questions.

CV: ASIANS ALOUD is more career-specific. What is the targeted age demographic? And was the film intended to speak to 20-somethings?

JY: “Asians Aloud” was meant to grab the broadest demographic we could, so we tried our best to cast a wide range of age groups (though they were all adults). It was our first shot at making a program like this and we wanted to have the best chance of appealing to a large group of people. There was (and is) no guarantee that we would have the money to do this again year after year, so we wanted to have the most reach possible.

CV: Between SMALL TALK and ASIANS ALOUD, which one is your favorite? And why?

JY: “Small Talk” is my current favorite, but any director tends to always like their most recent project. I did re-watch “Asians Aloud” at our HBO retrospective screening after not seeing it for years, and I was pleasantly surprised that some segments still held up for me – especially the Paul and James segment. I’m really happy with how that turned out.

CV: Do you identify as an Asian Pacific American filmmaker?

JY: I didn’t in the past. I wanted to be seen in life and work as simply an American. But being a part of this project has helped me realize that my culture really did shape who I am and how I approach my work.

CV: What is your trajectory as a director/filmmaker/dp? Any new works in the horizon?

JY: I want to be a part of projects that resonate with people. As a kid, I thought that I wanted to make quirky and weird films only for myself, but I quickly realized that it’s no fun being in a room full of people who don’t get my inside jokes. The best thing I did in film school was make a bad film that I had to defend all the time. I realized that what I love most about filmmaking is connecting with an audience and also learning from mistakes to make the next project better than the last.

As for new work, I’m working on a lot of commercial campaigns right now. I was hoping to make a web series with Maxwell Zen, who stars in “Small Talk.” Fans of the show on Twitter seem to think that’s a good idea. Now I just need to get him on board with the project, but I wonder if he will think it’s a waste of time. He’s going to be a big time CEO one day.

Jon Yi // www.jonathanyi.com