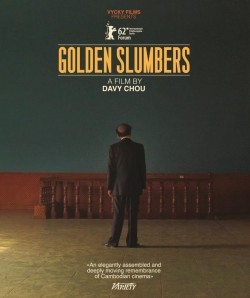

GOLDEN SLUMBERS: THE IMMORTAL STORY

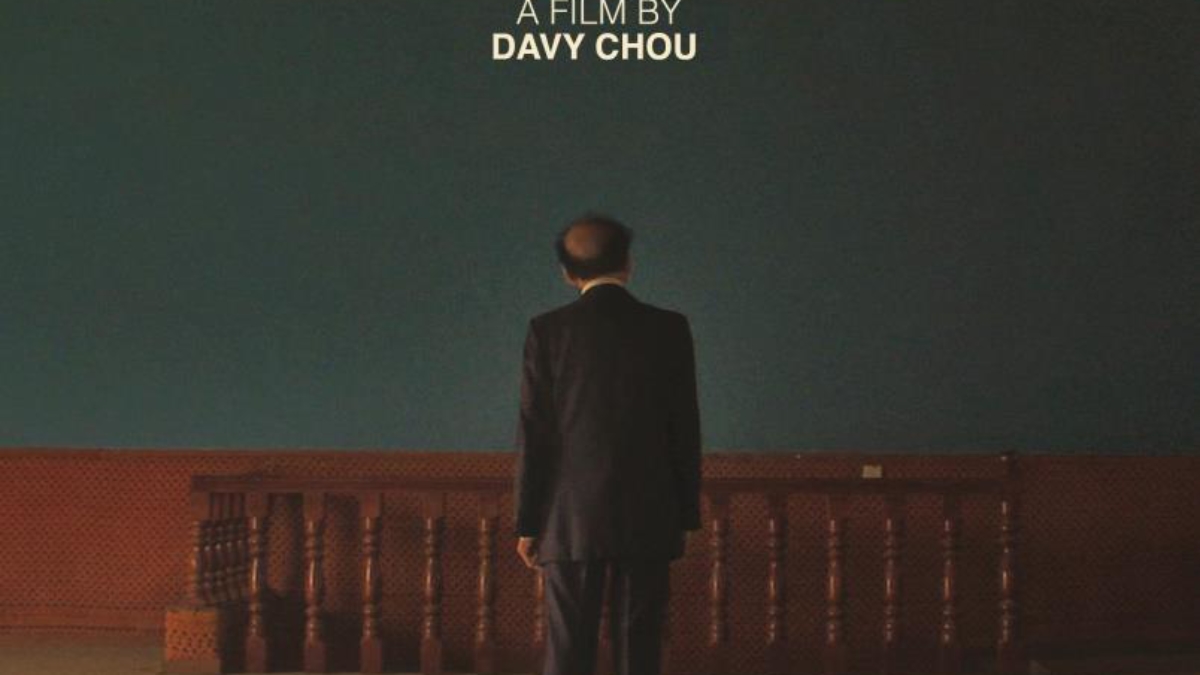

The oral storytelling tradition has existed since the dawn of human language. As long as we’ve been able to speak, we’ve been telling stories and passing them down from generation to generation. This is how we know the EPIC OF GILGAMESH and Scheherazade’s story of survival in ARABIAN NIGHTS. Over time, the way we’ve told stories has changed due to advancements in technology and the possibility of widespread exposure, but in GOLDEN SLUMBERS, director Davy Chou proves that this antiquated form of storytelling may also be the most enduring.

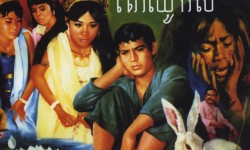

Imagine working as an actor or filmmaker during the Golden Age of cinema in Cambodia. You’re building a lucrative career for yourself while enjoying recognition from nearly everyone in your community. Then, as the threat of civil war slowly becomes a stark reality, everything starts to change. All people deemed “intellectuals” are forced into labor camps where they’ll be treated poorly and inhumanely, or otherwise be assassinated. Now your only job becomes survival.

This is the situation that the people of GOLDEN SLUMBERS found themselves in when the Communist Party Khmer Rouge took over the Cambodian capital, Phnom Penh, in 1975. Many lost their families, their spouses, and their children. All of them lost their life’s work. After Pol Pot and his army took over, theaters were destroyed and films were banned. Of the 400 movies produced between 1960 and 1975, only a handful survived, and in poor condition.

In GOLDEN SLUMBERS, Chou is more interested in preserving these lost stories than offering a commentary on war. He interviews the few survivors—including former actress Dy Saveth and filmmaker Ly You Sreang—all of whom share strong memories of creating the first great Cambodian films. As the documentary goes on, these positive memories prove more resilient than the negative.

Although physical copies of these stories don’t exist anymore, they survive through the oral storytelling tradition. Director Yvon Hem is shown in bed describing his movies and experiences to his grandchildren, who sit on the floor with rapt attention. Actress Dy Saveth revisits an old film site with members of the community, who share their perspectives from the day of the shoot. And through Golden Slumbers, the viewer becomes a part of this world as well after hearing fantastic tales about virgin demons, genies, and haunted hills.

In addition to these anecdotes, the film intimately examines various locations across Cambodia. Long, sweeping shots show former theaters that became karaoke clubs, restaurants, and shelters following the regime. Even shots of Phnom Penh look stunning as the camera pans across various streets and marketplaces.

While the beautiful footage of Cambodia grounds us in geography, the people ground us in emotion. At one point during the film, a Cambodian “cinephile” states that he can recall the names and faces of every actor and actress from the movies, but has long since forgotten what his brothers and sisters looked like. This is just one example of how Chou presents cinema as a form of escape. For these people, it’s an escape from war and turmoil which allows them to create art, entertainment, and lifelong memories in the process. With its gorgeous shots of Cambodia and the heartfelt stories shared by the brave filmmakers and actors of the 1960s-70s, Golden Slumbers more than measures up to this standard of cinema that it sets.

Contributed by Dan Toy