Written By: Sonny Arifien of Privilege of Legends

“If this were a TV mystery, then an important clue would pop up at this time …”

Has anyone seen Chan? He went missing back in 1982 and hasn’t been seen since.

It seems like a lifetime ago now, and yet some have never given up on that search. Others stopped looking long ago; putting it all behind them in an effort to get on with the rest of their lives. Still, on occasion they’re reminded of him whenever they step over a puddle in the pavement, or as they peer into a shop front window. Depending on who you happen to interrogate, their recollection of Chan may sketch a contradictory image from the account of another, and as a result his portrait has become the subject of multiple interpretations.

So who is the real Chan, and where on earth has he gone?

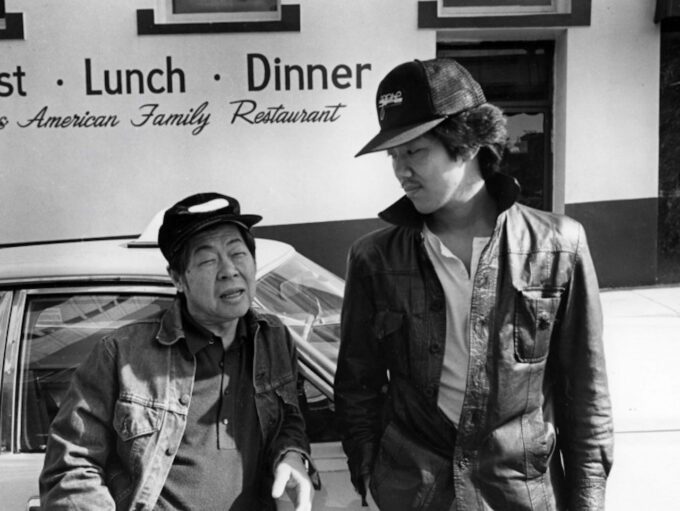

For taxi driver Jo (probably his American name), his reasons for wanting to track down Chan Hung appear straightforward enough from the onset of the film. He and his nephew Steve (we are told) had given Chan money to renew their licenses, and now that he’s disappeared so too has their money. The search leads the pair on a strange odyssey of sorts — through the kitchens, community centers and condominiums of San Francisco’s

Chinatown district. As they comb the streets for clues in an attempt to retrace Chan’s steps, the discrepancies send them down a rabbit hole that leaves them both soul-searching for an answer that is even more elusive than the figure of Chan himself.

Asking the question: “Who is Chan” to Hong Kong American filmmaker Wayne Wang would probably be met with a rhetorical one: “Who do you think he was?” You see, even if we don’t believe we’ve ever come across Chan personally, we might still have an image of him. To some, he may resemble an uncle or a family relative. Others might attach his image to someone that may have worked at the corner store or lived across the hall from them. He is both a stereotype and an anomaly; a walking and talking contradiction that embodies all of us and represents none of us at the same time.

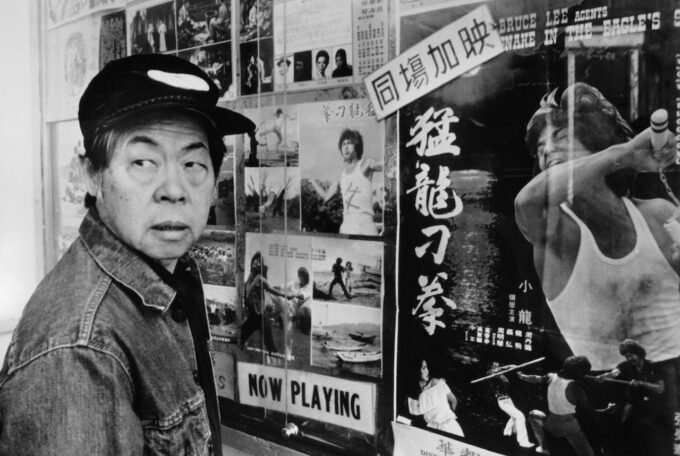

Once we separate the red herring of “Chan, the individual” from the notion of “Chan, the idea” the picture suddenly becomes more unambiguous and explicit. The name Chan may have derived from the mystery novels of American writer Earl Derr Biggers. His fictional protagonist, Charlie Chan became the inspiration for over 40 film adaptations, radioprograms, television serials and comics. The wise and benevolent Chan was a stark contrast to the derogatory “Yellow Terror” stereotypes that pervaded mainstream American culture at the beginning of the 20th century. But the character was still the embodiment of Western stereotypes, whether good or bad, and it’s depictions onscreen were almost always played by Caucasian actors in yellow face.

Another slightly less cryptic interpretation is Chan may simply be shorthand for Chinese American. The name is about as prevalent in Asian culture as Jones or Smith is in Anglo-Western culture, and by speaking in generalities, the filmmaker is able to feed into the broader cliché of America’s subconscious perception of its Asian population as a whole.

Growing up as an Australian kid with an Asian father, my half Eastern genes usually meant that I was identified by colleagues and peers alike as Asian. The fact that I’d only ever lived in Australia and had never been to Asia in my life never seemed to account for much. Whenever I happened to be asked where I was from and I replied with: “I’m from Australia,” the look I usually received was one of bewilderment; as if the truthful answer never appeared to satisfy them. The evidence didn’t match the clues, it seemed. If American-born kids of a non-white or Asian background can relate to this (and I suspect that many do) then they too have probably felt the internal contradictory tug of war that ensues when one stumbles into this grey zone of self-identity. Is it possible to be both American and Asian, and how much of one culture must you embrace (or lose) in order to do so?

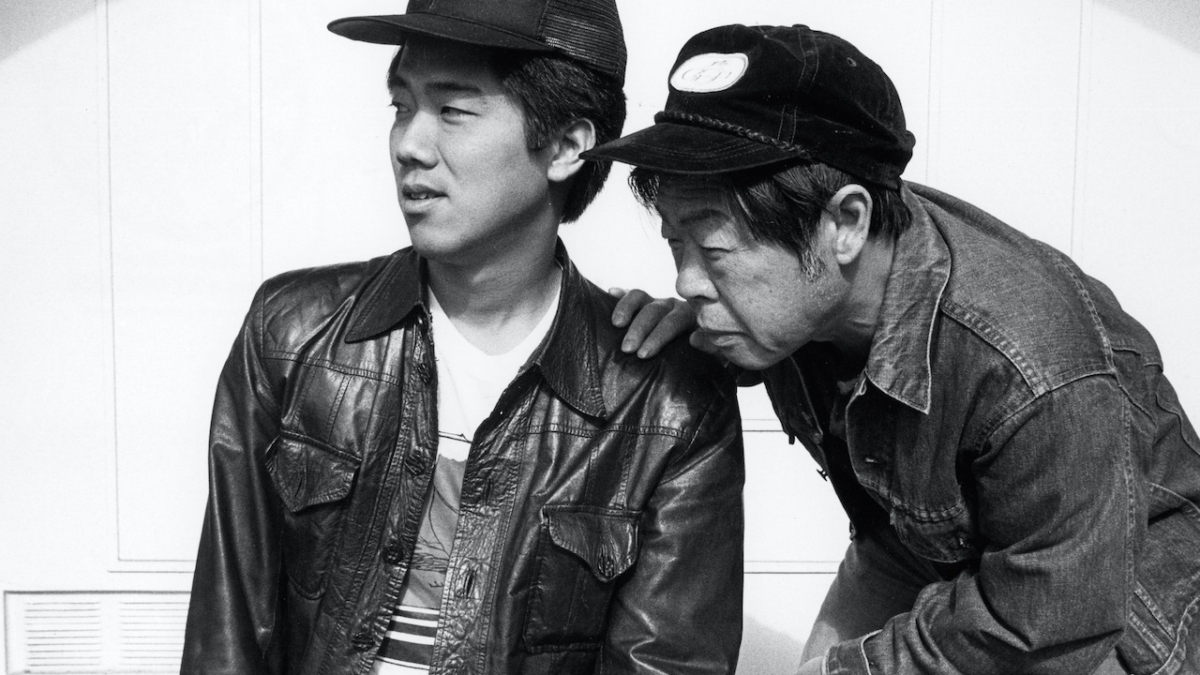

It is this unanswered question that seems to hang over Jo and his nephew Steve (played by Asian American Theater Company (AATC) members Wood Moy and Marc Hayashi) like a menacing cloud. Their difference in opinion on the subject causes conflict between them, and their views are challenged too by the opinions of those that they encounter along the way. In one memorable rooftop scene, Jo is conversing with an unnamed friend of Chan’s (described in the film as “the cook at the Golden Dragon who wears a ‘Samurai Night Fever’ shirt, drinks milk, chain smokes, and sings “Fry me to the moon,” all while he is cooking up five orders of sweet and sour pork”).

Jo’s cross-examination drags him into a broader debate on what it means to be a Chinese American. They question whether or not they’ll ever be accepted as Americans, or regarded as foreigners for the rest of their lives. When Jo argues that they need to “fight” it is met with a smirk. “Fight for what? Fight for recognition?” the man cynically asks, before continuing: “Half a million Chinese here for more than 100 years … they don’t want to recognize us.”

“Chan is Missing” was the first feature picture that Wayne Wang directed independently and is considered to be the first Asian American film to benefit from a wider theatrical distribution. Shunning his parents’ intentions of sending him to the U.S. in preparations for medical school, a 17-year old Wang (named Wayne after his father’s number one actor, John Wayne) embraced the art of filmmaking instead, eventually enrolling at the California College of Arts (CCA).

The Hong Kong-born director would regularly dip into the talent pool at the AATC in order to fill the roles for his early films. And there was no shortage of talented Asian American actors that were eager to play roles not restricted by the prejudices of appearance. This of course included Wood Moy and Marc Hayashi (who have exceptional chemistry together here in “Chan is Missing”) but extended to others like Victor Wong, Amy Hill, and former Miss Hong Kong, Cora Miao (of whom Wayne Wang would later marry), who would feature in Wang’s follow-up picture “Dim Sum: A Little Bit of Heart” in 1985.

“This mystery is appropriately Chinese. What’s not there seemed to have just as much meaning as what is there.”

Despite the pair’s detective work coming up short in the end, they didn’t exactly come away empty-handed. The money would be returned to them in full, and they’d come to a better understanding of their own individual identity as Americans. Those that overlooked the notion of Chan by searching for the individual would perceive the puzzle to be unresolved. But as the Chinese will tell you, they’re probably looking in all the wrong places.

This article first appeared on “Privilege of Legends.”