Revisiting Early AAIFF Films and Their Modern Counterparts

In curating this year’s archival program, programmer Hai-Li Kong sought to explore the limitless possibilities of film as a medium, selecting works that push the boundaries of how film can be manipulated and reimagined. “The goal was to recapture the pioneering energy that marked the early days of AAIFF by revisiting films that were first showcased during that period,” Kong noted, “In addition to these early works, we also include two films made in 2023.” By pairing these older films with contemporary ones, Kong emphasized that past works are not merely nostalgic curios; rather, they remain vibrant and continue to inform and engage with the artistic endeavors of today’s filmmakers.

Film As A Medium: 24 Frame Per Second (1978) and Eiga-Zuke (1994)

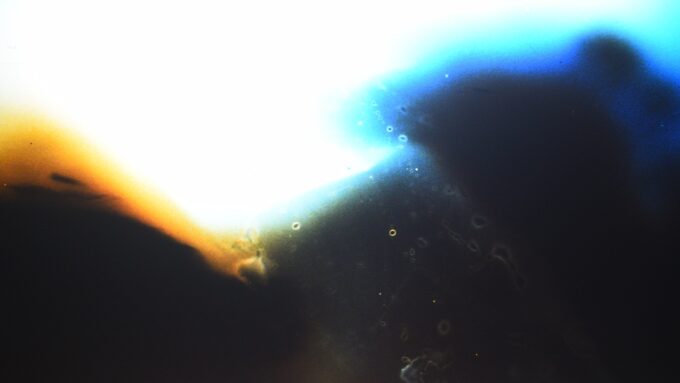

Director Al Wong uses extensive burning and writing in “24 Frame Per Second.” Everything seems intriguing and visually stimulating, yet it carries a powerful undertone of aggression. The shots written with pencil, marker, and brush give a perspective similar to that of the paper, a passive “being written upon” viewpoint. The entire film dismantled the illusion of continuity and integrity: the close-ups of various body parts deconstructing the wholeness of the body, and the burns appear to move like an animated cartoon due to the way movies show 24 pictures every second.

Sean Morijiro Sunada O’Gara uses Japanese pickling methods to create “Eiga-Zuke,” transforming the piece into a form of tsukemono. Much like pickles need time to ferment and develop their flavor, “Eiga-Zuke” highlights the Japanese tradition of waiting and preservation. This approach adds a unique depth to the work, especially when contrasted with modern society’s preference for quick and immediate results.

Reimagined: White Calligraphy, Re-Read (2010) and To Serve The People (1979)

Originally made in 1967 as “White Calligraphy,” “White Calligraphy, Re-Read” is a remixed and shortened version that director Takahiko Iimura developed in 2010. To initiate an experience unlike traditional cinema, Iimura’s work questioned and dismantled the semiotics of video and its relationship to the viewer. What makes a film experience, and what makes a reading experience? Iimura provoked the question by scratching characters from “Kojiki” (“Records of Ancient Matters”), an 8th century Japanese text about the creation of the world, onto the frames of 16mm black leader.

Danny Yung’s “To Serve The People” features only five distinct Chinese characters for the phrase “為人民服務” (“wèi rénmín fúwù”), which are superimposed in various combinations throughout the film. Introduced by Mao, this slogan embodies the core spirit of the Chinese Communist Party. It represents Mao’s critique of the old Confucian virtue of courage, which he criticized as being merely the courage to oppress the people and uphold the feudal system, rather than the courage to truly serve them. The upbeat, youthful music initially seems to support Mao’s slogan, like a marching tune. However, the rapidly flashing title cards feel more like brainwashing, leaving no time for reflection. Meanwhile, a child’s faint questions about the slogan are met with a woman’s assertive, dismissive responses, which effectively silences the child’s voice and any dissent.

Collective Memories: It Follows It Passes On (2023) and Natural Disaster (2023)

“It Follows It Passes On” reveals a familial anecdote with a Proustian touch. Constructed as a metaphorical bridge of memories connecting two landscapes and political entities, Kinmen — an island off the coast of Taiwan — has long served as a strategic military outpost, bearing the scars of historical conflicts between Taiwan and China. For the past two generations, the fragments of artillery shells in Kinmen, along with the recollections tied to them, have been an eternal death threat from across the strait. However, for director Erica Sheu and her generation, those shells are “teeth on the beach” — forgotten remnants, discarded and left behind. Sheu’s earliest memory is of a toy bowl falling onto the beach — echoing the dropped shells, the ordinary and the wartime. The burden of guilt inevitably lingers as one reflects on the hardships endured by earlier generations.

“Natural Disaster” is a found footage film that retells the turmoil within Asian families. Director Tiffany Jiang overlaps and juxtaposes footage to explore the complexities of family dynamics, with natural disasters serving as symbols of these intricate relationships. The connections between the images are subtle, relying heavily on Jiang’s text to weave them together. While the “family” is depicted visually, their identities remain intentionally ambiguous, allowing the film to resonate with a broader audience beyond its specific Asian cultural context. By blending definitions of these disasters with personal recollections of growing up in an unstable environment, the film captures the haunting, often unspoken tensions that shape familial experiences.

The “Celluloid Synergy: Experimental Films from 1960s-Now” shorts block screened at the 47th Asian American International Film Festival.